Martyn Joseph

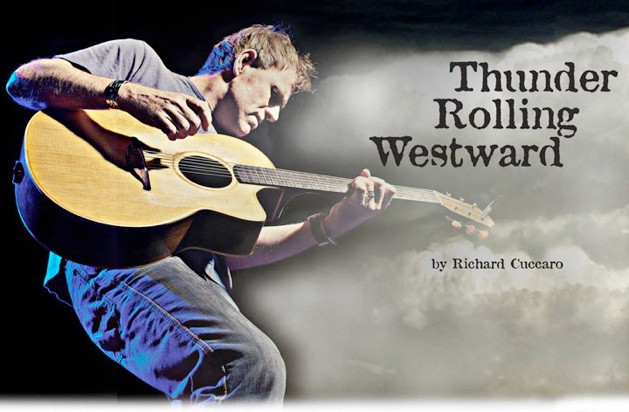

There’s something about him that takes hold of the audience as he steps onstage.

Standing about 6-feet-1, he moves in a way that seems towering. It’s not hard to re-imagine him as a giant nimbus cloud, his big baritone a low rumble of warning thunder.

The lyrics of his songs are bolts of metaphysical lightning. Martyn Joseph has come to sing for you.

In his 26-year career, he has sung all over the world. This spring he is taking his extraordinary gifts west from his native Wales to perform in the United States.

Those of us who have already made his acquaintance experience a thrill of anticipation as we wait to welcome him again.

He speaks truth, eloquently addressing the ills of a society gone mad and he speaks for me, in his iconic manner, with “Lonely Like America,” from his newest CD, Under Lemonade Skies, perfectly articulating the disappointment I feel in the corrupt fiber of my nation, rushing toward a tea party for the rich:

Redwood forest, Gulf Stream water / Stallion wild, Big Country sky

Cactus sculptures, widowed prairies / New York rains, and Texas dry

Frontier boom-towns of displacement / Scored a patriotic win

Your money bearing Rushmore’s giants / But your dollar’s paper-thin

I’m lonely like America … Land of less and more …

Lonely like America / Mythic, Graceland tour

The pioneers and racketeers / Sepia wagon trains

Across the Midwest plain … Lonely like America …

Beginnings

For one so gifted, the path to artistic brilliance did not come quickly. Martyn Joseph was born in 1960, in Penarth, Wales, about five miles from the capital city, Cardiff.

Martyn had no burning desire to play music in his early years. He was athletic and wanted to become a professional golfer. Apparently athleticism ran in the family. His father, a local sportsman, played rugby for Cardiff. Martyn won golf tournaments as a youngster and at his peak, had a handicap of one.

He’d buy records, like every other kid. His tastes ran to Led Zeppelin and Elvis. He liked the melancholy in Elvis’ voice and recalled to me some of his favorites: “Suspicious Minds,” and “The Wonder of You” among them. He also took particular notice of Elvis’ Rock and Roll Hall of Fame-member lead guitarist, James Burton. When he was 10 years old, he saw Glen Campbell play an Ovation guitar on television and asked if he could get a guitar. Additionally, a teacher in school played guitar and sang songs and had something of an impact.

His father bought him a guitar, but insisted that he take lessons, so Martyn took lessons in classical guitar for about three years. That first guitar was of the typical flat-top steel string variety, so, to make matters easier, after one year, he got the wider-necked classical type.

The guitar stayed in the background (but active) all the while as he played in golf tournaments. His musical talents would emerge persistently. Martyn played in local shows connected with a church youth group, while never having any sense that this would be what he would do with his life. He also performed in school concerts, playing Spanish classical pieces solo at one concert and at another as a member of a rock band. There were also local Eisteddfods, a more traditional type of festival, where he performed as well. Some influence reached and found him across two generations. His grandfather, who belonged to a older gentleman’s group that got together to sing old songs, showed him chords on the piano. His grandfather owned records by Tom Jones and Max Boyce. While Boyce was primarily a comic performer, he also recorded more serious songs about the struggles of Welsh miners, which had an impact on Martyn.

The Performer Emerges

“Around 1975, I was 15 years old and was still involved with this church youth group. I wrote a series of five or six songs about a young kid who was going through a tough time with drugs. We put the songs together in a presentation over a few nights. We had a choir and a few actors. It was well-received and a few people began telling me that I should take a serious look at singing and playing.”

This was very ironic, since at that time Martyn was failing his course in music at school. He found the stories of great composers and the intricacies of their work boring. There was no practicality in it. The idea of making a living doing music seemed a stretch. “There was certainly a dichotomy there,” he says.

Having received encouragement, he went into a small studio in Cardiff and made a demo tape of the songs he’d written for the youth group production, plus a few more that he’d also written, then sent them to music publishers. He got back a few positive messages of encouragement, but nothing more, until a new company, Eyes and Ears, offered to pay for half the cost of production of a record. They were looking for new talent who could help foot the bill for their costs.

It was time to make a choice: golf or music. At this point, Martyn took a hard look at his golf game. He recalled: “My standard of golf was pretty good, but it was never going to be good enough to be a star.”

Martyn was working part time for his father in the ceramic tile business and turned to him for half the money to make an album. He wrote some new songs and in 1983, his debut album, I’m Just Beginning, was released.

The Faith, then The Doubt

The 1970s and ‘80s marked the emergence of the contemporary Christian music market. Eyes and Ears had contacts in the church scene in the U.K. and booked Martyn into many church coffeehouses and at the Greenbelt Festival (at the time, a primarily Christian festival held on a farm in Suffolk, U.K.). In the United States, Amy Grant and Keith Green were stars in that genre. Martyn listened to their work with a keen interest. Within the next few years, Martyn became “quite a big fish” in the U.K. part of that market. This happy arrangement lasted almost a decade.

As a result of his popularity in the Christian music world, around 1988, Martyn was approached by Tearfund — a relief and development charity working in partnership with Christian agencies and churches — to write songs to help solicit donations. Tearfund took Martyn to Thailand to view the poverty there. Martyn’s rosy view from inside the cocoon of religious thought was shattered. In his book, Notes on Words, he states: “I guess we view life from wherever we stand, and my vision had been a little blinkered and comfortable to that point. There was a leap from writing quite positive upbeat material obsessed with answers and very few issues, to songs that explored questions, contradictions and the political. There were many reasons for this, but I think one of the main contributing factors was my visiting the Third World for the first time and sitting with people who not only lived in abject poverty but also had no legitimate means of doing anything about it. As I sat there with them, I remember thinking that I couldn’t go home and write in the same way anymore.”

Additionally, one member of the administration at Ears and Eyes had embezzled funds and shortchanged musicians. When Martyn found out, his view of the world widened, and it now included many of life’s seedier aspects.

The New Road

The first album to exhibit Martyn’s evolved viewpoint was, coincidentally, his first U.S.A.-produced album, Treasure the Questions (1988). Martyn had been on tour with the Christian rock band White Heart. The bassist Tommy Simms, close to embarking on a producing career, offered to produce Martyn’s next album, and Martyn accepted. The title track illustrates the new direction: I treasure the questions as they rage in my mind / I treasure the questions some day I will find / I ran out of answers such a long time ago / And I treasure the questions wherever I go.

A follow-up live album, An Aching and a Longing (1989), further accentuated Martyn’s widening perception of the human condition. As its title track states, life’s viewpoint and directions can oftentimes be boiled down to a simple equation: … Just an aching and a longing To be loved / Loved with dignity, whispers deep inside of me / A million years away from what the experts have to say / We don’t know nothing / We don’t know much / Just an aching and a longing / To be loved.

The Evolving Songwriter

Martyn’s first song to make the English charts was “Dolphins Make Me Cry,” heard initially on Treasure the Questions and included on his major label (Sony) 1992 release, Being There. Taken verbatim from his wife’s reaction to dolphins at an aquarium, the title gives a false impression about the nature of the song. Not a melancholy ballad about dolphins, it is rather about the general way the human race squanders the beauty of the world: They say we learn by our mistakes then we carry on / Sometimes I’m not sure … Did you ever touch the loneliness of a broken man / Did you ever see a starving child die / Do we really do these things to one another / Do you see why … dolphins make me cry.

Martyn’s second and last album for Sony, Martyn Joseph, contained another chart single, “Let’s Talk About It In The Morning.” Here, Martyn stretches farther afield, delving into the disintegration of a marriage: We’re props upon a stage / and our lives have disengaged / and we never seem to laugh / and you never clean the bath / Let’s talk about it in the morning …

The following album, his first for Grapevine, Full Colour Black and White, contained the song “He Never Said,” an in-your-face throwdown to the hypocrisies of modern life, both secular and religious: He never said Archbishops should stick to theology / He never said put your faith in the lottery / He never said by any means necessary / He never said my country right or wrong / He never said send your money to me / Touch the screen and you’re gonna be healed …

Tangled Souls (1998), his second and last for Grapevine, contains “Strange Way,” one of the most daring metaphoric meditations on the life of Christ and the crucifixion … Strange way to hang around for hours / Strange way to imitate a kite / Strange way to get a view of Auschwitz / Strange way to represent the light / Strange way to watch for stormy weather / Strange way to disprove gravity / Strange way to go about fund-raising / Strange way to sing I’m liberty … Strange dissident of meekness / And nurse of tangled souls / And so unlike the holy / To end up full of holes.

Pipe Records

There are some songs so excruciatingly beautiful they beggar description. One of these is “Have An Angel Walk With Her,” an impassioned cry for help for those whom life’s better fortunes are not attainable: Free in my thinking but slave to my thoughts I am, I am / Have an angel walk with her / And the demons stay with me / Some who walk this earth / Are not meant to be free…

Another is “Can’t Breathe.” Your beauty steals everything / runs through me / Am I alone? This silence I am so frightened I am a prodigal who’s too scared to run home / Why can’t I, can’t breathe / falling down… The effectiveness of the falsetto coming from that big voice on the words “can’t breathe” is a wondrous surprise.

The Legacy of Welsh Miners

Part of Martyn’s political consciousness was forged in the struggles of the Welsh miners. They were among the first to fight against the tyrannical yoke of company and government overseers. “Dic Penderyn,” the story of Richard Penderyn, a man falsely accused and hung for injuring a soldier during an 1831 uprising, eloquently tells the tale: He slowly climbs the steps to the gallows pole / The last few moments of a life … And the wife of a Richard Penderyn / Supported there, too weak to stand / Disbelieving anger and sorrow / For her innocent man, an innocent man / She says, lift me up, oh lift me boys / Let me see the one I love / Lift me up, oh lift me now / Let me see the man I love one more time …

Martyn pays homage to the legendary American singer and blacklisted activist Paul Robeson, who supported many workers in their struggles, in particular, the miners of Wales. Robeson holds a special place in the hearts of Welsh miners and their descendants. In the 1940 British film Proud Valley, Robeson portrayed a black American “David Goliath,” who works, sings and stands with them in their time of need. Taking some elements from the film, some from life, in “Proud Valley Boy,” Martyn sings in the voice of an old Welsh miner in the 1980s after the mines had closed, leaving him to learn typing in a re-training course. The miner thinks back to a time when: A giant came here once / And he shone like ebony … A dragon came here once / Back home some cursed his name / They tried to quench his fire / This David and Goliath in one frame …

War and Hypocrisy

“The Good In Me Is Dead” bears witness to the indiscriminate brutality of war on civilian populations. It focuses on Bosnia, but Martyn has added verses in concert to reflect losses in New York and Afghanistan: In the hills of Prestina, my family worked the land / The images flow through my ticking mind, and fall like grains of sand / My brother’s in those hills now, I saw him lying there / His eyes they did not see me, as my fingers touched his hair / As I kissed his dirty hair / If this is all that’s left now / There’s nothing to be said / And the good in me is dead.

The first YouTube video I saw of Martyn (and there are many) was “How Did We End Up Here?” It was written during the Bush administration. The lyrics should be printed in history books, just so we never forget: We make the enemy confess / Jesus wearing battle dress / chain them up and make them crawl / bang his head upon the wall / salute the troops, grave concern / body bags, we never learn / why interrogate the soul? / if Dr Strangelove’s in control / 2 more years! woo hoo! / woe to us, woe to you / think of all the oil revenue / how did we end up here?

There are too many jewels in Martyn’s repertoire to cover here. Some of the later albums that I downloaded, Deep Blue (2005), Vegas (2007), Evolved (2008) and the aforementioned Under Lemonade Skies (2010) show how his songwriting has kept pace with folk audiences’ hunger for stronger poetic expression of personal and universal themes.

This is a voice that is big enough to connect with stadium audiences. We in the New York area are fortunate to have a chance to see Martyn in some intimate settings. At the Kerrville festival, we’d sure like to be around any campfire where Martyn shows up.

We encourage everyone to see this giant talent. Put off that family picnic, skip your birthday this year, change the date of that wedding. Whatever it takes, DO NOT miss this guy.

Upcoming U. S. performances include:

May 12 Christopher Street Coffee House, 81 Christopher St., NYC

13 Empire State Railway Museum, 70 Lower High St., Phoenicia NY

14 Music on 4, house concert, upper west side, NYC

15 Acoustic Celebration, Temple Shearith Israel, 46 Peaceable St., Ridgefield, CT

29 Kerrville Folk Festival, Quiet Valley Ranch, Kerrville, TX

Website: martynjoseph.com