“Crazy Horse, we hear what you say: one earth… one mother… One does not sell the earth the people walk upon. We are the land. How do we sell our mother? How do we sell the stars? How do we sell the air?

— John Trudell, “Crazy Horse,” Bone Days

The earth is in trouble. Its inhabitants are in danger. Industrialists who rape and pillage the globe for resources and riches control the government and its courts. Some dissidents have had the courage to stand up and say, “Stop… no more.” Many have paid with their lives and many have been Native Americans.

On Feb. 11, 1979, after years as a Native American activist, recoiling from U.S. government duplicity and the systematic genocide of his people, John Trudell burned the American flag on the steps of the J. Edgar Hoover Building in Washington, D.C. Twelve hours later, on the Duck Valley Indian Reservation in Nevada, John’s pregnant wife, Tina, their three children and his mother-in-law were burned to death in a fire at their home. The FBI, having already amassed 17,000 pages of files on Trudell, declined to investigate. Officials in the government-friendly Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) concluded that it was an accident. This strains credulity beyond the snapping point. As John told journalist Cynthia Oi (Honolulu Star-Bulletin) in 2001, “Murdered … it’s very simple. They were murdered.”

After hiring his own arson investigator who concluded that an accidental fire spreading so quickly was impossible, Trudell took to the road with a friend, fleeing in a state of temporary madness. In this manner, a poet was born.

He has said that “lines” came to him while his friend drove. He wrote constantly, reeling his sanity back in. After one year, he published a book of his writings, Living in Reality — Songs Called Poems. He began publicly performing recitations from the book with traditional singer-drummer Quiltman. After meeting Jackson Browne he started recording with Browne’s help. Later he met legendary Kiowa guitarist Jesse Ed Davis (sideman to Browne, Bob Dylan, John Lennon and The Rolling Stones), who helped him coalesce his words with music.

I acquired his early recordings, A.K.A. Graffiti Man (1992) and Johnny Damas and Me (1994) in the late 1990s, after hearing a live radio appearance with free-form New York DJ Vin Scelsa. Today these recordings resonate with ominous prophetic vision as the corporate overlords of the United States of America Inc. increase their grip over every aspect of our lives. Other recordings released over the years offer additional wisdom on a metaphysical level.

“Johnny Damas and Me,” the title track of that CD, presents an aural vision of John after the fire, in flight from his pain. The track begins with a snarl from a distortion-boosted lead guitar and is braided with a tribal chant that expresses grief and anger. He seems to be presenting multiple facets of himself as he flees: Johnny Damas and me, and the mongrel dog / we’ve been layin’ real low / in the shadow of the road … high on a hill / the reckless wind knocks, rattling the night … in a home not his own / over his shoulder, watching the door / ready for flight, needing to run…

Now, like an addict, I listen to him over and over, releasing his personal agony and exploding invective against hypocritical leadership. I get one hit after another of rage against forces I can’t control. I get another hit of sorrow for fallen warriors and lost causes.

Over the hey-hey-heya chant of Quiltman, John recites in electrifying, passionate couplets and triplets: In the Nazi Babylon … Lucifer dances with angels … and the dead carry the living on their backs. It took me a long time — a year or two into the reign of Bush the younger — before the meaning of “Nazi Babylon” sank in. So much of the song’s content became relevant: Ruthless and arrogant … ride the pale pony [harbinger of death] … using hatred [or fear] as a shield. His horrific memories are alluded to: Something still doesn’t settle … This can’t happen to me … I don’t carry it well … [who could?].

The majesty of its swirling tower of rage and sorrow leaves me stunned and saddened. It’s a perfect storm, a billowing thundercloud of premonition and dread. It speaks of what has happened and what is yet to come. His words are more relevant today than ever.

Today, John Trudell, the Gil Scott-Heron of Native Americans, almost single-handedly lights a torch of truth in the darkness, illuminating the hazy perceptions of a society gone mad in confusion. He performs with his band Bad Dog and speaks to audiences … about thinking as opposed to blindly believing; about what it means to be human; about fighting the robotic corporate mindset; about becoming attuned to the earth’s needs, as our tribal ancestors were. John has been ahead of the curve for so long, so far out in front of the rest of us, it’s a miracle he’s retained his sanity. It must get lonely out there.

Our Internet research uncovered the rocky trail John followed to his destiny.

Beginnings

John was born in Omaha, Nebraska in 1946, the son of a Santee Sioux father and a Mexican mother. He grew up in the Brazil Creek District of the Santee Sioux Reservation in northern Nebraska near the southeast corner of South Dakota. He was educated in local schools and also in Santee Sioux culture.

John’s mother died when he was 6. At that point, an attempt was made to introduce God into the equation. This did not fly with John.

In high school one day, he was called into the principal’s office. He was told that he had potential, but that he needed to study harder if he wanted to make something of himself. John states: “That’s when I quit school. I realized that we weren’t operating on the same level of reality because I knew that I already was something.” He knew right there that he needed to get out of the Midwest. In 1963, at 17, John dropped out of high school and joined the U.S. Navy, basically to escape its deadening mentality, to “survive.” He served during the early years of the Vietnam War and stayed in the Navy until 1967. He says he made the right choice, “because the Vietnamese didn’t have a navy.”

Afterward, he attended San Bernardino Valley College a two-year community college in San Bernardino, California studying radio and broadcasting. Before long, he put his studies to good use. An event occurred some 436 miles away in San Francisco Bay that would change the course of his life.

Alcatraz and AIM

In 1968, the Indians of All Tribes organization occupied the deserted Alcatraz Island, formerly the site of the infamous federal prison. They were claiming property that, as formerly Indian land, having fallen into disuse, was supposed to be returned to them according to the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty agreement. Members of the American Indian Movement (AIM), established in 1968 in Minneapolis among urban American Indians, joined them there. John went to Alcatraz and joined the occupation. Possessing a rich, reedy baritone and an acute sense of injustice done to his peers and ancestors, he was born for this. He became their spokesperson, creating the “Radio Free Alcatraz” station with the help of Berkeley College students. His broadcasts, at night over the Berkeley FM station, exposed the widespread poverty on the nation’s reservations and U.S. government’s overall lack of support. The Indians of All Tribes wanted nothing less than the entire island as a Native American cultural center and university.

In the middle of negotiations, U.S. marshals, ignoring the agreed-upon process, swooped in and forcibly removed the Indians. However, a symbolic flare had been shot skyward. Native Americans on reservations across the nation were galvanized to see that their views were being articulated.

John then joined AIM, serving as chairman from 1973 to 1979.

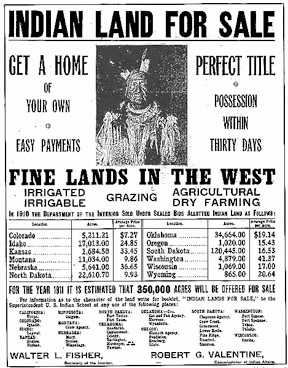

Touchstones in History

As I researched the circumstances surrounding the activities of John Trudell and AIM, I kept encountering earlier historic examples of U.S. government perfidy regarding broken treaties and usurping of Indian lands everywhere across the continental U.S. Overrun by the deluge of settlers determined to wrest the land away from its occupants by any means possible, they were squeezed into smaller and smaller spaces. The Black Hills in South Dakota carry particular significance. When General George Armstrong Custer reported finding gold during an 1874 expedition, settlers poured in, illegally squatting on land considered sacred Native American ground. President Ulysses S. Grant secretly turned a blind eye to this blatant breach of contract.

The Battle of the Little Big Horn that killed Custer and his men in June of 1876 was a result of the U.S. Cavalry’s attempt to force the Lakota Sioux and Cheyenne back to their reservations as they tried to follow the buffalo and avoid starvation.

Wounded Knee Massacre of 1890 Following the Custer debacle, another sortie was made, against the Lakota Sioux by U.S. soldiers. Again, the issue was their “failure” to stay confined to a specified region. Soldiers escorted a tribe from an off-reservation hunting expedition to the Wounded Knee location. With the intent of confiscating firearms, they surrounded their encampment. According to the account in Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee by Dee Brown, on the morning of December 29, 1890, in a struggle with a tribesman who spoke no English, a shot was fired. The soldiers wildly opened fire. Tribesmen fought at close quarters with knives, clubs and pistols and soon needed to flee. Big Hotchkiss guns on the hills opened up on them, shredding the teepees with flying shrapnel, killing men, women and children.” Fleeing women and children were then shot as they ran. A three-day blizzard rolled in that evening and afterward, a burial party found 300 bodies lying under mounds of snow, frozen into grotesque shapes.” This grisly incident was considered to be the end of the “Indian Wars.”

The Path to a Deadly Backlash

It was during the 10 years from 1969 to 1979 that the FBI amassed its 17,000-page dossier on John. A series of escalating events brought death to many Native American activists.

• The Trail of Broken Treaties Caravan The U.S. refusal to recognize broken treaties and live up to legal agreements is at the heart of the injustice toward Native Americans. In 1972, AIM led an automobile caravan of 250 tribes from all over the United States to Washington. They occupied the headquarters of the Bureau of Indian Affairs for five days. Their “Twenty Point Position Paper” demanded sovereignty over their lands. They hit a brick wall. Then-president Nixon, embarrassed by the takeover, rejected any treaty reform and paid out $68,000 for gas money to leave. The tribes decided they’d done all they could do and left.

• Wounded Knee incident The contingent that returned to the Oglala Sioux Pine Ridge Reservation in the southwest corner of South Dakota was met with resistance from tribal president Dick Wilson who vowed to keep AIM off the reservation any way he could. AIM stayed. Pine Ridge residents who desired a return to a tribal system asked AIM to remain there because they were being bullied (rapes, beatings) by Wilson and his private militia “Guardians of the Oglala Nation” (GOONs). Pine Ridge was perhaps the poorest reservation in the country. Wilson was criticized for favoring family and friends with jobs and benefits and using tribal funds to create his private militia in order to suppress political opponents. After a failed attempt to impeach Wilson, AIM occupied the town of Wounded Knee, chosen for its historic significance. On Feb. 27, 1973, a 71-day armed standoff with U.S. law enforcement began. Following deaths on both sides, the occupation was called off. Wilson remained in office.

-

•The Oglala Incident Open conflict between AIM and Wilson’s GOONs continued and resulted in the deaths of many AIM members The murder rate between 1973 and 1976 was 170 per 100,000. It was the highest in the country. In the middle of this conflict, on June 26 1975, two FBI agents drove into an AIM compound setting off a firefight. The agents were killed and two AIM members were tried for the agents’ deaths in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. In the face of a media campaign to paint the AIM activists as terrorists, John Trudell stepped forward and spoke on behalf of the men and AIM. His wife, Tina and other women met with church groups to show the human side of AIM. The two AIM members were acquitted. A third AIM member, Leonard Peltier, was extradited from Canada, where he had fled, and convicted to two life sentences. Evidence was later found to be false or tainted, but a new trial has not been granted and he is still in prison. Incident at Oglala, a 1992 documentary produced and narrated by Robert Redford, attempts to exonerate Peltier.

The Fire: An Incalculable Loss

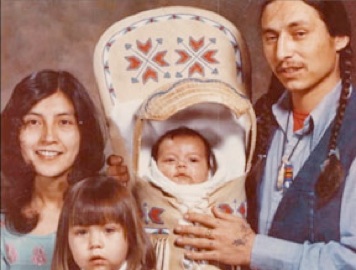

Tina Manning met John Trudell while she was a psychology student at the University of Tulsa. John had a speaking engagement there. She saw what his mission was and fell in love with him. After they married,Tina told John that she’d accompany him on the road for just two years; then she wanted to return home, where she could work with the people there. A lifelong resident, Tina was trusted by elders and regarded as a leader in her own right. Contamination of water and land on reservations from commercial and governmental mining operations is still a large issue, resulting in abnormally high rates of cancer and other illnesses. Tina had been a tribal water rights activist in the community, spearheading tribal initiatives without asking for government permission. Tina’s father, Arthur Manning, who survived the fire, was a member of the Duckwater Shoshone Tribe’s tribal council. Her mother, Leah, coordinated social services at the reservation and was working for treaty rights. There were local BIA leaders and others who were hostile to the Manning family and might have had a motive to torch the house (perhaps with prodding).

John has said that attributing the fire that killed his family solely to his own actions is to diminish the work of his wife.

Tina and the children were buried together. Her name and the children’s names are on the headstone. Their unborn child’s name, Josiah Hawk, is inscribed under Tina’s name. John has said: “I died then. I had to die to get through it. And if I can get through it, then maybe I would learn how to live again. Putting my love into the ground like this… Putting my love in boxes … putting them into the ground reconnected me to the earth.”

From Poetry to Music

Wikipedia states: “About six months after the deaths of his family, Trudell started writing. He describes his poetry as the following: ‘They’re called poems but in reality they’re lines given to me to hang on to.’” John has said that they were a parting gift from Tina. The craft that he created is something that has evolved. It’s like a form of non-rhyming rap, set against Native American percussion and chants.

After John published Living in Reality, he continued speaking and began to link forces with influential, high-profile musicians. In the documentary on his life, Trudell, made by filmmaker Heather Rae, released in 2005, John can be seen in film clips being introduced by a very young Jackson Browne at a No Nukes rally to speak to the thousands in attendance. John has given Browne credit for turning his life around, giving him entry into the recording industry.

The first set of songs with Quiltman, Tribal Voice was recorded to cassette and “released” by conducting a giveaway at the Duck Valley Shoshone-Paiute Reservation in Nevada. It was then mailed out to purchasers.

Kiowa guitarist Jesse Ed Davis was staying at The Eagle Lodge in Long Beach, California. The lodge had a copy of Tribal Voice and Jesse listened to it. John was doing a reading nearby, so Jesse came to see him and volunteered to put his words to music. John had been unsuccessfully looking for someone exactly like Jesse when the motherlode of guitarists walked up and introduced himself (Jesse, a top-flight session man and John Lennon favorite, took the lead guitar solo on Jackson Browne’s hit song “Doctor, My Eyes”).

John found a spiritual brother in Jesse. Unfortunately Jesse was a heroin addict and died from an overdose three years after he started working with John. Their three albums together were AKA Graffiti Man (1986), ... But This Isn’t El Salvador (1987) and Heart Jump Bouquet (1987). Mark Shark ably took over as lead guitarist for John’s band. To date John has released 13 albums. The music on each is at once both raw and elegant. Themes on the albums range from ecology to straight-ahead love songs. On AKA Graffiti Man, “Tina Smiled,” is a slow elegy of devotion: Last time I saw her, Tina smiled / Woman, woman’s love, hands so gentle, eyes so wise … Somewhere a wild horse listens …

The Warrior on Film

John’s activism led him to be given a lead role in perhaps my all-time favorite film, Thunderheart, directed by Michael Apted, who had also directed Incident at Oglala. The film has folded in much of the Oglala Incident and Tina’s mission. It contains so much of John’s message that I believe he has to have assisted in writing a lot of its dialogue. He certainly wrote his own lines in the moment where the FBI agent played by Val Kilmer confronts the falsely targeted fugitive, Jimmy Looks Twice, played by John. Part Native American himself, Kilmer’s character sympathetically tells Trudell’s character: “They’re gonna kill you if you stay here.” John replies, “Sometimes they have to kill us.” It seemed like overheated bravado in that moment when I first heard those words. It wasn’t until many years later that I understood the complete truth of that statement — until I understood the terrible price anyone labeled a dissident must be ready to pay. John finishes his role with: “There’s a way to live with earth and a way not to live with earth. We choose the way of earth.”

When he speaks, John can be Gandhi-like: “No matter what they ever do to us, we must always act for the love of our people and the earth.”

I don’t know if it is too late to live up to John’s ideals. As a race, we seem to have drifted so far from our natural state, so far into consumerist, industrialized beings. Whatever our fate, it is imperative that we give this man a listen. Mother Earth is bleeding and she needs us.

Website: johntrudell.com