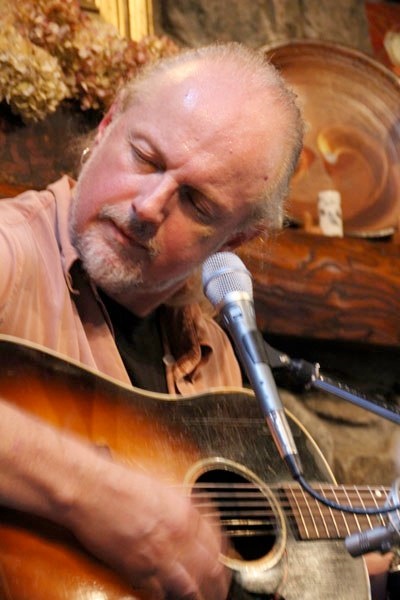

Garnet Rogers

The Long Road to the Here and Now

By Richard Cuccaro

Some dreams are more real than wakeful life. The story in this one starts with a low electric hum. On a Fender Stratocaster, harmonics drift in, echoing high, like something floating above. A percussive rhythm is set up, the right hand pinching and striking the strings at once. The sound loops and flips, like a kite in a stiff breeze. The voice slides in, rich and dark, like burnt umber: How bright the stars, how dark the night / how long have I been sleeping? Canadian icon Garnet Rogers is singing his song, “Night Drive,” about a dream of his brother Stan, who perished years before. Stan is alive in the dream, as if he never left: I saw you behind the wheel / on this very road I’m taking… Your eyes were keen and bright in the dashboard light / dreaming of the westward ocean. The listener is pulled along on that road with them both: I know this road and its every curve / where the hills commence their climbing / We rested here, if my memory serves / the Northern Lights shining… It is exalted and sorrowful all at once. It’s Garnet, but not all of him. He has outrun sorrows in his life and he sees the ridiculous in everyday existence — mainly in his life. He’s quick to share as much of it as he’s able, every time he performs. Was it that way the first time I saw him? It’s hard to remember all of it…

Meeting Garnet

In 1997, I was new to my current day job in Manhattan as a computer graphics artist. I was also the volunteer manager at the Fast Folk Cafe in TriBeCa, which catered to the singer/songwriter genre. Sometime that year we got lucky and booked Garnet. By this time, most fans in our little circle knew about Garnet’s brother, the iconic Stan Rogers, and his tragic early passing. Stan had written elegiac songs about the working class in the Canadian Maritimes and farms, and had a rich, deep baritone. It sounded like the guy had a kettle drum for a chest.

Garnet inherited pretty much the same vocal instrument and wrote songs with a wider variety of themes. I’d heard enough to know we were in for an evening of great music. What I didn’t know was that the day of the show, I’d be fielding anxious messages from Garnet, left on the cafe’s phone answering machine throughout the day. He didn’t know that we were completely volunteer-run and truly manned only on evenings when shows were scheduled. Wondering why nobody was there to answer the phone, he repeated his concern with each message, as to whether there would actually be a show. As he approached from somewhere north, the sound of his voice got more and more agitated as he got closer and closer. He wasn’t leaving a phone number, so I believe he was using pay phones en route and there was no way for me to reassure him. After work, I made a beeline for the cafe to make sure someone was there when he arrived. Somewhere between 6 and 6:30 p.m., he came striding through the door, carrying two guitars — six-and-a-half feet of irritated Canadian. I was able to explain the situation and he appeared mollified. A new dilemma revealed itself as he continued to carry more guitars in, followed by electric amps that made him look like a one-man Pink Floyd tribute act.

Our upstairs neighbor had been at war with us over the sound levels. Her kitchen sink, located directly over the cafe’s stage, allowed her to put a hose from the sink into a hole in the floor and send a torrent of water onto performers during their show. On two occasions I had run to the basement during a show to shut off the building’s water main. However, our neighbor was softening, aware that I’d been working on the ceiling, trying to remedy the situation. Taking no chances, though, without saying anything to Garnet, I grabbed $40 from our bank and ran upstairs. I asked if she’d allow us to buy her dinner and a night out (until, say, 10 p.m.). With a bemused smile, she agreed. The evening went off without a hitch. Garnet was his typically majestic self, filling the room with sounds the walls had never felt before. As he made his exit that evening, I remarked at how well the night went. With a now-familiar self-deprecation, he said, “Yeah, after I got over my hissy fit.” Years later, we had a chat before he did a Lincoln Center Out-of-Doors concert and I told him about that night and the woman above the cafe. He laughed and I posed the idea for a feature article. He was agreeable, but it wasn’t until we saw him this past fall at Tim and Lori Blixt’s Cabin Concerts (Wayne, N.J.) that I felt ready.

Beginnings

Garnet’s mother and father came from Nova Scotia, but moved to Hamilton, Ontario to find work. They were fans of country and folk music and, as youngsters, had listened to Carter Family broadcasts from a powerful border station in Mexico during the ’30s. Garnet and his older brother Stan grew up in Woodburn, a community in the easternmost part of Hamilton. They listened to Grand ‘Ole Opry from there. “There were these incredibly powerful 50,000 watt AM stations in the ’30s, ’40s and ’50s, Getting Grand ‘Ole Opry was a dawdle for us. It was magic,” he said. At night, Garnet and Stan practiced their harmonies on songs they’d learned.

Writing ran in the family “My aunts and uncles wrote songs; some wrote poetry. Music wasn’t something you just heard on the radio. It was actually what you made yourself. We got the idea very early that you could make sense of your life and maybe even have some fun writing songs about what was going on locally.”

Stan and Garnet were of one mind with their parents when it came to music. “We had Woody Guthrie records, and Odetta and Leadbelly. My mother was crazy for Bob Dylan. She managed to wangle tickets to see him at Massey Hall. That was the very first concert I went to. She and Dad took me and my brother. I was in grade three. It was one of the seminal moments of my life. [Dylan had just gone electric, provoking violent reactions from purist folk fans.] I thought, ‘Oh my God, this is what I want to do.’ I didn’t necessarily want the tension or the weirdness, but to be in the middle of something that exciting was like heroin.”

As the boys grew up, radio played a pivotal role in their development as musicians. Garnet recalled, “We had this great radio station in Toronto. At any given hour, you’d hear Frank Zappa, Duke Ellington, Phil Ochs… Frank Zappa would be on for an interview, then they’d play Schoenberg … no rhyme or reason, no sense to anything … it was just music. There was also a great Detroit station we used to listen to. Hamilton was about halfway between Detroit and Buffalo. Those Motown groups would come through. You’d have Martha and the Vandellas, Sam and Dave, Wilson Pickett, all on the same bill. They’d play some little theater and your head would explode. Stan, older by six years, got to see them. He’d come home and report to the younger Garnet. One night he returned with this weird look in his eyes like Charlton Heston as Moses with his hair turned white, coming down from the mountain. He said, ‘…Wilson Pickett just wrote The Ten Commandments with his finger!’ Stan was in a little rhythm and blues band when he was in high school. That stuff just got into your DNA.”

High School in the Woodshed

Garnet had to teach himself. He had wanted to learn the building blocks of playing the flute and learn how to read music, so he briefly attended a class in 10th grade for that purpose. The teacher told him he’d have to join the high school marching band to continue. “I didn’t want to have to play John Philip Sousa marches and the guy told me I didn’t have any musical aptitude anyway, so I buggered off,” Garnet said.

Garnet continued his development behind and parallel to Stan. They were listening to and being influenced by the same people. “He was starting to write the odd good song and he’d come home to use my machine to record them, so I had that to work with.”

On-the-job Training

Garnet started getting on stage with Stan when he was around 14. A great believer in playing out, he stated, “You can spend three hours practicing scales by yourself and you’re not really learning; but if you spend ten minutes on stage wondering where all those notes are and how you’re going to make them count, that’s a much better way of learning an instrument. By 16, whenever Stan had a local gig, I’d sit in for a bit if it wasn’t a school night. Stan was in college when that was going on.”

After Stan was signed by RCA records to do some novelty singles and they went nowhere, he moved to London, Ontario, which was closer to Garnet. Garnet started commuting every weekend because there was a club there that he liked, Smale’s Pace. During the folk revival of the early ’70s, a raft of singer/songwriters gravitated to London because of the great club scene. Stan became part of that community. Garnet was younger, but was included. He’d go there just to see who was playing. Afterward, the evening would turn into a giant jam session, everyone sharing new songs. “It was pretty fertile,” Garnet said.

During the last two years of high school, Garnet was part of a strange, interesting concept. “A bunch of people decided that they were going to put together a sort of ‘supergroup’ of singer/songwriters and some sidemen and take it out on the road as a band. There would be 12 to 17 people onstage at any given time. It was an interesting idea, but in practice, it was like trying to herd cats. Nobody rehearsed. We had two drummers, two bass players, a sitar player … For God’s sake, we had an interpretive dancer at the side of the stage who wore black tights and whiteface.” Garnet was part of the band and played local gigs, but still in high school, he couldn’t do road dates.

The Road Years with Stan

At first, the gigs were in bars in northern Ontario. Guys came to the bars to get drunk, not to listen to sensitive guitar players singing about life. Being large men, they got used to the idea that they’d have to fight to play their music. Garnet likes to say, only half-facetiously, that they’d have to fight their way on-stage, off-stage and back to the hotel and that they developed a middle set that was nothing but sea chanteys which left their hands free to defend themselves. One recent blog entry from Garnet reads: “…re-connected with a guy named Rob Schmidt who was present and remembers and corroborated the details of my brother’s arrest for attempted murder of an audience member in Jasper, Alberta so many years ago... Now THAT was a magic night .... happy days!”

Their fortunes changed along with their sound. As Garnet stated elsewhere: “The Maritime traditional sound we developed was a response to partly the market and partly simply due to the commissions we were given by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. We did a lot of soundtrack work for radio dramas and a lot of it was in Halifax.” From that point forward, Stan’s reputation grew as the six albums produced during his lifetime were released.

John Gorka’s song, “That’s How Legends Are Made,” a tribute, captured Stan and the band succinctly: The band was a bass man / And a brother on lead / There was no more / ’Cause there was no need / So fine to see / What they could give / ’Cause legends call us to live … Hard work, magic / Then some tragic end / And so a legend begins.

The end came just after the band played the 1983 Kerrville Folk Festival in Texas. All three band members had planned to go home on the same flight, but only Stan wanted to stay the extra few days after the festival. The other two were road-weary and homesick and took earlier flights. Garnet was already home when a television news broadcast told about the flash fire that trapped Stan during an emergency landing, killing him presumably of smoke inhalation. It was the very same plane Garnet had flown home a couple of days earlier. “It could have been any one or all of us,” Garnet told me.

Solo Touring and Discography

Garnet didn’t have any immediate plans to honor already scheduled gigs, but a call from a venue in the U.S., saying that they still wanted and expected to see Garnet, provoked action. Now it was Garnet, by himself, who had to come up with the songs. Along with the grind of the road, Garnet had to process the loss of his brother and his brother’s growing legend. The temptation of drinking that often follows many a solo touring musician was actually a continuation of his time with Stan. It appears that he got out of the gate by doing covers. On the first album I bought, Speaking Softly in the Dark (1988), Garnet comes as close as I’ve heard him sound like Stan, on “Like a Diamond Ring,” by his friend, Steve Hayes, one of the number of songs by other songwriters. He uses a softer inflection and longer sustains on the vocals, like Stan did. There’s an instrumental he wrote and a poem by Henry Lawson that he set to music. Of the four albums Garnet sent me, I like the studio albums, Firefly (2001) and Shining Thing (2004), the best. He had come fully into his own by the time of these albums’ releases, settling into a muscular, chesty vocal sound, and had long begun building his own storehouse of songs. “Where’d You Get That Little Dress” on Firefly offers proof that if he wanted to settle into a blues groove, he could ride it all the way to the bank. Similarly with “Ease Into It” on Shining Thing. Without any identification, he might be mistaken for Dave Alvin. “Twisting in the Wind” could give Tom Russell a run for his money. Shining Thing also may be his most romantic album. “Soul Kiss” was written for his wife, Gail. He also seems to have her in mind on “First Day of Spring,” “Here Tonight” and his cover of Edwin Starr’s “Oh How Happy.” I’d be remiss to not give praise to his live album, Get A Witness (2007), with its perfect, scathing portrayal of our most recent President Bush in “Junior.” Witness also has a live version of “Night Drive,” played as a trilogy with Bruce Springsteen’s “Blood Brothers” and Stan’s “Northwest Passage,” as he often does in concert with a band.

In Concert

Garnet sprinkles his between-song patter with stories and cutting, wry humor that audiences carry home and share with others. At the Cabin Concert he told about how he began talking onstage about getting sober, soon after his three days of cold turkey in a motel room. He put it out there to make sure others knew and so he wouldn’t fall back. He added: “After I quit, I got a letter from [Scotch whiskey manufacturer] Glenfiddich, asking, Was it something we said?’’ These days, he also reads from the memoir he’s working on of his days with Stan. It’s R-rated and hilarious. In an email, he described how one story got this response: “[folksinger] Steve Gillette came up to me after a show and told me he enjoyed the reading but now had a very curious nine-year-old grandson who wanted to know what kind of person a ‘drag queen’ was, and just what was a ‘hand job’? ... Must have been a fun drive home…” We heard the story referred to at the Cabin Concert, but I won’t reveal the details and spoil the fun for future audience members. He used to speak more about his vehicles (“The Stealth Volvo”), but that was absent during the last swing. I went online for one of these older stories: “Two years ago after wearing out four Volvos I got to the point where I didn’t want to support my mechanic’s extravagant lifestyle,” he said, without even a hint of a chuckle. “After I sold my Volvo he had to sell one of his Lear jets.”

Garnet’s story is so rich and he’s such a great musician (his blues fingerpicking on “Corrine, Corrina” might be the best I’ve ever heard) that this article should span two issues. But there are others waiting in the wings. We’ll simply have to implore our readers to see Garnet live and buy every album he’s released. He’s simply unforgettable.

Website garnetrogers.com

Upcoming Performances

Feb 9 7pm The Walkabout Clearwater Coffeehouse White Plains, NY

22 8pm Bearsville Theater - Woodstock, NY

23 8pm Peterborough Players Theatre - Peterborough, NH

Mar 2 8pm Hurdy Gurdy, Fair Lawn Community Center - Fair Lawn, NJ