The Making of a Legend…

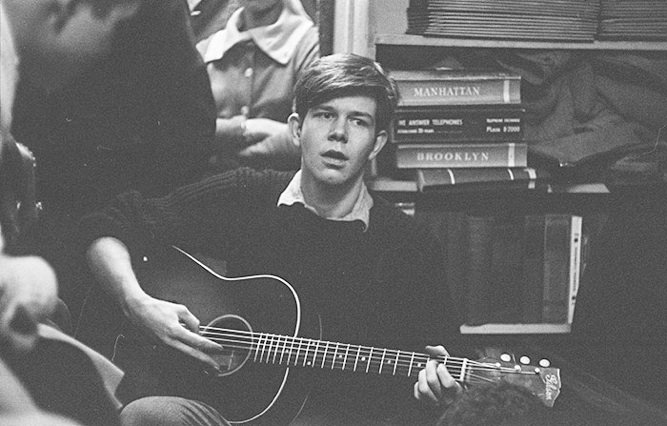

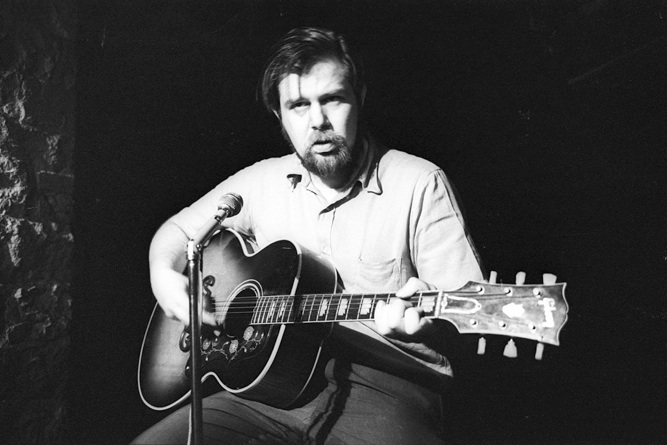

Dave Van Ronk

by Richard Cuccaro

For a moment, a chill swept over me. It was about a half hour before I was to meet Dave Van Ronk at the Cornelia Street Cafe to learn more about him for this feature article. I realized that I was about to sit down and talk with this giant presence, a living monument to everything worthy of respect in folk music. Full of intellectual curiosity and fire, he's paid his dues, studied the masters in jazz and blues, remained true to his own ideals and in the process, created an enviable body of work, of both his own songs and of those he admires. He's still performing, recording and teaching, and he's still his own man.

To sit and talk with him is to hitch a ride on an odyssey; a wild, bumpy ride through a life of self-discovery and fulfillment.

It was 2pm. sharp when I walked into the Cornelia Street Cafe for my meeting with Dave. He was there already, seated at the bar, in front of a beverage of the caffeinated variety, talking to Ron Cohen. Ron is a friend of Dave's who is involved with the Folk Museum of Greenwich Village and author of Rainbow Quest, a book about the folk revival. We chatted for a while about a number of things, including a series of hoots to be held at the museum, and then Ron left.

As with all of our feature subjects, I wanted to know the particulars about Dave's early interest in music. I knew from Dave's bio that he was born in Brooklyn in 1936 and developed an early interest in jazz. What had gotten him charged up and thrust him in that direction?

The Childhood Years

It turns out that his mom and dad had been separated and he'd boarded with a woman named Emma "Mom" Hogan from the age of four until he was eight. His mom lived nearby and saw him every day after work before returning to her rented room. At Emma's house, the radio was on all the time and, as Dave told me, "I was a musical carnivore." Dave said that he found out much later, that she had operated a speakeasy for Legs Diamond when she was younger. She'd done some rum-running for him as well; making pickups outside the city and driving the car back to New York surrounded by cases of booze. She was a big fan of jazz players, especially those she had met at the speakeasy. A tune would be playing on the radio and she'd exclaim, "I know that guy!" Naturally, young Dave soaked all this in. During the '40's Fats Waller, one of Emma's acquaintances, had a live radio show in New York, so of course, Dave became a big fan of his. There were other live broadcasts from ballrooms as well-- among them, Count Basie, Benny

Goodman, and Eddie Condon. Dave said, "I knew who these people were, the way kids learn about their favorite ballplayers."

When he was eight years old, he and his mom moved to Richmond Hill, Queens with his grandparents. By this time, heavily into jazz, he remembers listening to Ted Husing's American Bandstand as well as a variety of "small combo" and Dixieland shows, one of which featured a New Orleans style jazz band, he recalled, with a chuckle,"The Chamber Music Society of Lower Basin Street."

At around the age of twelve, Dave began playing the ukulele during resurgence in its popularity. Radio and TV talk show host and talent scout Arthur Godfrey gets some credit here. Later he would start playing a guitar that was given to him. He started with just four strings, treating it like a big ukulele, then gradually he added the other two strings.

Is it Jazz or is it Blues?

He was also collecting jazz records. Louis Armstrong was a particular favorite. At some point, he was shopping around and came across the first Riverside 10-inch LP (he still has it), Louis Armstrong Plays the Blues. At first he was annoyed to find that it wasn't Louis by himself. Louis was backing people like Chippie Hill, Ma Rainey, and Ida Cox. It turned out that he liked it a lot. From there, he started collecting and listening to blues artists. While most of them could only be found on 78rpm singles, there was one 10-inch LP called Listen to Our Story. It was mostly ballads, but there were two that could be taken for blues, They were "Staggerlee," played by Furry Lewis, and "True Religion," played by Reverend Edward Clayburn, both fingerpicked guitar pieces. Dave thought he was hearing two guitars in "Staggerlee." When someone told him it was one guy using 3 fingers, he is quoted as saying, "I went berserk trying to figure out how it could be done. I practically tied my fingers in a knot."

Washington Square…Finally

Somewhere in his late teens, after assiduously avoiding the folksingers in Washington Square for years, he finally saw Tom Paley (of the New Lost City Ramblers) playing there. Fingerpicking. "I think he was playing 'Railroad Bill.' I said'Aha!' A light bulb went on over my head! When he finished up, I asked him, 'How do you do that?' Damned if he didn't take the time to show me!" This began a five-year period in the mid fifties where Dave hung around Washington Square and met up with other players, learning the craft. One of these players, and his biggest influence, was the blind Reverend Gary Davis. Gary would come to the square and Dave would jam with him and "he'd show me stuff." Dave says he learned "chords, fingerings and voicings and never would've learned how to play in the key of F if it wasn't for Gary."

An important source of learning the craft of playing folk came from Harry Smith's Anthology of American Folk Music. Dave emphasizes the impact of this huge LP archive upon the young folk aficionados of his day, stating that all the young players were listening to and learning from it. He bemoans the tendency of singer/songwriters today to ignore traditional music. He emphasizes: "There is a collective American unconscious. Songwriters who tap into it create songs that have a resonance." Here he mentions Greg Brown and David Massengill as positive examples. " Those who ignore it create works that are ethereal, with no bottom. So petit bourgeois, so suburban… They just float…"

Leaving Home

From the age of 17 on, Dave had been coming into the city from Queens, sharing cheap rented apartments with other players on the Bowery and later, uptown, mainly for the purpose of partying. When music as a career became a goal, he was keeping company with other people in their 20's who had the same idea. For most of these people, this was strictly a bohemian interlude. They were middle-class kids who'd been to college. When the opportunity presented itself, they gave up the bohemian lifestyle and got jobs and careers. In Dave's case, he'd come from a working class background and did not have anything to fall back on-- music was his "ticket to ride," as he told me.

The Great Traditional Jazz Revival

For a time, Dave straddled the fence between blues and jazz. He'd been sitting in, playing the guitar, at clubs, like the Stuyvesant Casino. Famous players like Johnny Hodges and Coleman Hawkins would come in. Dave also went through a period where he tried to earn a living as a banjo player in the traditional New Orleans style of jazz. Although he was interested in modern jazz at the age of 12-- his favorite guitarist was Charlie Christian- - at around 15 years old he became convinced by critics that it was derivative and commercial and that the only pure jazz came out of New Orleans from the turn of the century to 1916. In a Sing Out interview he states" 'I came into Manhattan with my Vega. I weighed 240 pounds.

Six or seven months later, with the assistance of my great passion for traditional jazz, I weighed 170." He hadn't realized that the revival for traditional jazz was at its end. When asked why he thought he could make a living from it, he replied: "I didn't

have the sense God gave a duck. I never had starved before; I had no idea of the great number of possibilities out there in the world, one of them being starvation."

Origins of Folk in the Village

Around 1954-5, while still playing jazz occasionally, Dave tilted more heavily toward playing folk music. In the mid 50's, Sunday nights would roll around and, after the action in Washington Square ended around 7pm, Barry Kornfeld held a hoot at the American Youth Hostel on Eighth Street and everyone would troop over there. When that ended at 10pm, they'd go over to Roger Abraham's place on Spring Street and the music would continue 'til 4 or 5 in the morning. That lasted until another occupant got fed up and everyone got thrown out.

A short time later, a place opened on Third Street called the Cafe Bizzare. It was one of the first coffeehouses in the Village to have folk music, Dave says, preceding The Gaslight and the others by about a year. It was here, later, that Dave experienced a turning point in his direction toward becoming a folk singer. During this time, Dave was getting some valuable performing experience by participating in the Folksinger's Guild series, usually held at the Sullivan Street Playhouse. Folksingers would produce their own shows on "dark nights" (Sunday or Monday) when no plays were scheduled. Singers would get anywhere from a half-hour to an hour on stage, depending on whether there were two, three or four acts on the bill.

Around this time, there was a folk series called the "Midnight Special" once a month taking place at the Circle in the Square, #1 Sheridan Square — featuring performers like Odetta, Josh White, Cynthia Gooding, Oscar Brand, Jean Ritchie, and Theodore Bikel.

Dave wanted to play in shows there. He said: "I figured if I got in there, I'd be farting through silk … These people were the 'establishment' — I thought they were rich." It wasn't until he got to know them that he found out that their lifestyle was anything but luxurious.

Shipping Out, then Dropping Anchor

Looking for gigs during the fifties, Dave saw places that made an attempt to put folksingers to work but had no license for live music. He played a little in bars along Eighth Avenue, for pass-the-hat money, and that'd more often than not was spent at the bar. Busking was frowned on by the police. This entire situation simply held no future, so Dave got his merchant seaman's papers and shipped out. That's what he figured was going to do for a living. After a couple of long voyages spanning about a year at sea, Dave came home to find the Cafe Bizarre hopping with people who were playing to real audiences. Flush with several thousand dollars from both his pay and winning a large pot in blackjack aboard ship, he decided to stick around, and throw in with them. He wound up as one of the opening acts there for Odetta.

She later told him he should sing professionally and if he'd make a demo tape for her, she'd get it to Albert Grossman, her agent (and later, Bob Dylan's manager) who was running a coffeehouse in Chicago (his first involvement with folk) called The Gate of Horn.Dave made the tape and, after a while, hearing nothing, hitchhiked to Chicago to see Albert. (Dave found out much later that a friend who was supposed to give the tape to Odetta had forgotten to do so.). When he got there, 48 hours later, high on benzedrine tablets, he then found out that Albert had never received the tape. He was asked to audition but failed to get a gig.

Furious, he set out to hitchhike back to New York. During his first ride, he fell asleep, and when he woke up, his wallet with the rest of his money and his seaman's papers were gone. Somewhere on a long stretch of Indiana highway, between Chicago and New York, he decided it was time to start his career as a folk singer. When he got back to New York, he couldn't take a ship for six months, and had to earn some money.

The Van Ronk Career Takes Root

From 1957 to '59, Dave continued playing around Washington Square and occasionally at The Folklore Center but still wasn't making any real money. A trip to California in 1959 brought some steady work for the first time. He went for what was to be a one-month trip and stayed for three, playing gigs at the Insomniac Coffeehouse in Hermosa Beach and at Herbie Cohen's place, The Unicorn, on Sunset Strip. He then came back to New York thinking that he'd hang it up as a performer and just teach guitar. Walking down MacDougal Street, he happened to run into a friend, singer/actor Jimmy Gavin, who asked if he wanted a job. A place called the "Commons" needed players on a steady basis. The next thing Dave knew, he was playing there six nights a week, for the next six months.

Dave Van Ronk, Booking Agent

After a while, the other two players sharing the bill left, leaving only Dave. In a panic, the owner asked him if he knew others who wanted to play. So he became the defacto booking agent. Jimmy Gavin performed there with Bob Gibson, another seminal figure of that time who was an influence on many. The one really major figure who would become a steady act there from then on, thanks to Dave, was the Reverend Gary Davis. Gary would come in around 4 or 5 to have dinner and Dave would pick his brain. When Gary took the stage, Dave would be there, front and center, watching every move, every lick. This lasted for about a year.

In the winter of 1960-61, Dave moved from his place on 15th Street to an apartment on Waverly Place in the same building as Barry Kornfeld. The building was filled with musicians. Barry was the Reverend Gary Davis' sidekick and Gary was at the apartment a lot. Dave made it a point to be there as well, picking up more licks. Bob Dylan crashed many a time at Dave's apartment here while learning his "folk" chops, many of them, in guitar, from Dave.

The Posthumous Lesson

Dave tells a story about a dream he had, many years later, two years after Gary had died. He had never completely understood how Gary played the "F" part of "Candy Man." He dreamed that he was performing and Gary was on stage with him. When he reached the "F" part, in the dream, Gary leaned over and showed him exactly how he played it. When Dave woke up, he checked the fingerings he remembered from the dream against the recorded version and he had gotten it!

The 60's Folk Explosion

At this point, In the early sixties, college students around the nation were embracing the left and the civil rights movement was taking place. This was the petrie dish in which folk music began to grow. Dave turned down an offer to be part of the trio, Peter Paul and Mary. It wasn't his style. The slot was filled by Paul Stookey.

Dave started getting more and more work.The late Lena Spencer, of Caffe Lena in Saratoga Springs in upstate New York, used to say that Dave had to have played 20 or 30 weekends per year in '60-'61.

The Gaslight, in Greenwich Village was originally a poetry room, and while they had singers, they weren't featured at first. Folksingers used to pass the hat for their pay. Eventually, though, it became like a second home to Dave. He says that every once in a while, he and the owner would get into a fight and he'd get fired. He then knew he'd be getting a raise, because he'd stop back a couple of weeks later, and the owner would say, "Where've you been?" Dave would reply, "You fired me!" The owner would shoot back, "Well, you're hired, again!" Then, Dave would say "Well, my price has gone up!" They'd settle and, after a short vacation, Dave was back at work, with his well-earned raise figuratively tucked in his back pocket.

Gerde's Folk City, originally called The Fifth Peg opened in '60 or '61, and was booked by Izzy Young, of the Folklore Center. It became an important landmark, and while Dave got more work at the Gaslight than at Gerde's, he became an important part of The Folk City scene also.

The big festivals came calling, too and Dave did them then, and still does, today. While he has said he's not overly fond of that type of large-crowd setting, he did do Newport, along with Dylan and Seeger and was a staple at the Philadelphia Folk Festival in the sixties, doing 2 or 3 years in succession before taking a year off.

For The Record…

Dave's recording career started in 1959 and then rolled onward. The money started pouring into the Village, and a lot of people were getting recording contracts. Peter, Paul and Mary, Bob Dylan and Dave as well. From 1959 to 1961, Dave recorded for Folkways, putting out the LPs Dave Van Ronk Sings Ballads, Blues and a Spiritual, and Gambler's Blues.

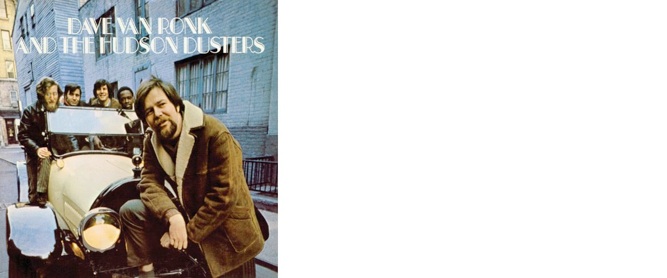

The same records were also released under the titles Black Mountain Blues, Dave Van Ronk Sings Earthy Ballads and Blues, and Dave Van Ronk Sings The Blues. In subsequent years he recorded Dave Van Ronk, Folksinger, In The Tradition, and Inside Dave Van Ronk for Prestige, and Just Dave Van Ronk and Dave Van Ronk and The Ragtime Jug Stompers for Mercury. All of these are considered classics today. He kept right on going — in many stretches, putting out an album a year. His total output, containing other"must-have" albums, numbers well over twenty, the titles too numerous to mention in this small space.

I must mention however, Dave's Going Back to Brooklyn (1985) for a marvelous sampling of his original work, including possibly the best anti-war song ever written, "Luang Prabang," also covered by Patrick Sky on the notorious album Songs that Made America Famous. Dave wrote it in the very effective form of a traditional Irish dirge and he sings it a capella. As promised in the printed newsletter, here are the lyrics:

Luang Prabang

When I got back from Luang Prabang

I didn't have a thing where my balls used to hang

But I got a wooden medal and a fine "hoorang"

And now I'm a fuckin' hero

Mourn your dead, land of the free

If you want to be a hero, follow me

Mourn your dead, land of the free

If you want to be a hero, follow me

And now the boys all envy me

I fought for Christian democracy

With nothin' but air where my balls used to be

Now I'm a fuckin' hero

Mourn your dead, land of the free

If you want to be a hero, follow me

Mourn your dead, land of the free

If you want to be a hero, follow me

And one and twenty cannon thunder

Into the bloody wild blue yonder

For a patriotic ball-less wonder

Now I'm a fuckin' hero

Mourn your dead, land of the free

If you want to be a hero, follow me

Mourn your dead, land of the free

If you want to be a hero, follow me

In Luang Prabang there is a spot

Where the corpses of your brothers rot

And every corpse is a patriot

And every corpse is a hero

Mourn your dead, land of the free

If you want to be a hero, follow me

Mourn your dead, land of the free

If you want to be a hero, follow me

--© Dave Van Ronk

The Odyssey Continues

He's still going strong and is currently working on an album of jazz pieces. The folk/literary world is still waiting for his autobiography. In one recent interview, he tells of a visit from Bob Dylan. He came home to find Bob in his living room. His wife having let Dylan in ("I've told her not to do that," he is reported to have said, wryly). He told Bob, "I just got back from the supermarket." Bob replied, I wish I could do that." Dave then told the interviewer, "I could always use more money, but I don't need any more fame." Today, as he moves about Greenwich Village, unrecognized by the general populace, his followers will always react to him with a respect bordering on reverence because they know they're looking at one of the treasures of American history.

For a good place to find out more about Dave, try the Jeff Kenney website, Dave Van Ronk Unauthorized at:

http://web.archive.org/web/20070204232641/http://www.culcom.net/~shadow1/

It has all the major interviews and links to other items of interest (guitar arrangements, fan sites, photos, booking) about Dave Van Ronk.

Thanks, Jeff!!

Dave Van Ronk passed away on February 10, 2002, a little over a year after our interview and this profile was published. I'm grateful to have had the privilege to speak with him at length about his life and career.