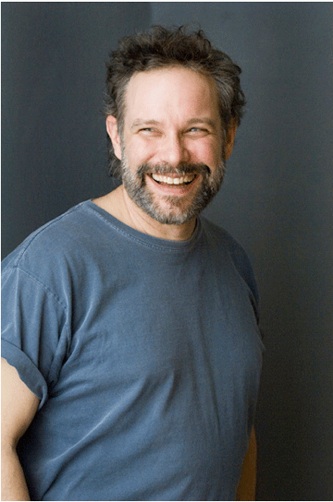

John Gorka

…cutting a path through the darkness

by Richard Cuccaro

If any of this works for you, then John Gorka is your guy. He’s the one who gets it better than everybody else, and delivers it in a voice so rich, it makes Pavarotti weep.

How you pick your favorite John Gorka song(s) can say a lot about you. Where do you start? He’s written so many great ones, it overwhelms the mind. At around 1996, when I realized that I didn’t have the tools to be a performing songwriter, I figured I might be happy singing Gorka covers for the rest of my life as a music feature at poetry readings. I learned just one before my vocal chords sent in a letter of resignation: “Love is Our Cross to Bear.” I never got to the other ones that stacked up like cordwood. When I sing them, in my head to myself, they roll in, one after another in an almost endless chain, then loop around and start repeating.

It says something about me that two of my favorite Gorka songs, occurring back-to-back on the 1994 album Out of the Valley, explore the dark side of John’s psyche. Like all of his songs, every line is cut and polished like a diamond.

The first is “Bigtime Lonesome.” It describes the pulling apart of a couple in which the woman, unsatisfied with her wandering partner (John, himself?), sends him packing when he proposes. A slide guitar keens mournfully as he sings, “He got back the ring with the note she sent / when he tried to make it permanent … and if you live your life with your baggage packed / It seems you leave more often / than you come back… When love’s a storm moving down the line / how can you dream any more of the future time / No sound from the pillow by the window sill / between her and the call of the whippoorwill.”

The second is a dark rumination on potential loss called “Furniture.” In a minor key, over a rolling Michael Manring bass line, he sings: “What good am I if I leave you lonely / What good am I, if I’m lonely too / What good is a one and only / if that one and only’s leavin’ you / Am I losin’ you? / Am I losin’ you? / I know you’re lonely too…”

The emotional terrain was all too familiar when I first heard it and, though life has been good -- I’ve been gifted with a loving, solid marriage -- the darkness still calls to me. Even the hopeful ending carries with it all the years where the light seemed far off. “Hope comes from the smallest places / little rooms inside the heart / the furniture there bears the traces / of every unsuccessful start / unsuccessful start, it’s like a work of art / the bottom of the heart…”

John’s dark, comedic sense shines on two other songs on the album, “Mystery to Me” and “Up Until Then.” Here we encounter his trademark sarcasm and laser-sharp perception of human foibles. I like those a lot, too, just not as much as the melancholy ones (my bad).

In the early ‘90s, I first became aware of performers in the singer/songwriter field, after discovering WFUV-FM and its “Cityfolk” program. The voices and names poured out of the speakers: Greg Brown, Shawn Colvin, Cliff Eberhardt, Lucy Kaplansky and … John Gorka. Much of what was played was generously sprinkled with “graduates” of the Fast Folk Musical Magazine stable of discoveries. A lot of them had played at the Speakeasy, a Greenwich Village venue on MacDougal Street. When that closed in 1992, Fast Folk’s founder, Jack Hardy, looked for two years and found a space in TriBeCa to provide a listener-friendly place to play. He called it the Fast Folk Cafe. I heard about its imminent opening and headed down to help. A year later, Jack headed back out on the road to get back to his career and left the cafe in the hands of volunteers. The cafe was foundering financially and in danger of closing. At a critical juncture, with rent money lacking, John Gorka was booked to play. He filled the room, pulling in enough money to keep the cafe going. Lucy Kaplansky came in to provide backup harmony. John sweated profusely and seemed to be suffering from a cold. He hesitated between songs, appearing to try out a new persona, “the slow guy.” This brilliant performer haltingly spoke his song introductions, causing Lucy to look at him quizzically. The hesitancy is not an affectation. It’s just the way he’s most comfortable expressing himself. However, he acknowledges that it can work in his favor, as a comedic effect. My favorite moment occurs during shouted requests. He’ll listen to the names of songs and respond, “I recognize those names as songs I’ve written…” In other words, “there are too many to sing, and I’ll do the ones I want to do.” It’s an unusual audience member who goes away unsatisfied.

John soldiered through his Fast Folk Cafe performance and the cafe survived for another four years until the lease ran out (giving the landlord the opportunity to charge higher rent to a carpet store -- also now defunct). That show lives on for me as one of the most memorable (and there were many).

John was born in 1958 in Edison, N.J., about a half-hour outside of New York City, and grew up a little bit north of Edison in the town of Colonia. As a youngster, he was aware of the power of language. He states: “I knew I wanted to be a writer before I knew that music was going to be the route I’d take. I was moved and impressed by the power of words. When I started to try songwriting I realized that through music I could express more than I could through words alone. It is the closest thing to a complete form of expression.”

John took an early interest in banjo and, through his brother, got interested in guitar. An online description states that “he got his first guitar as a Christmas gift, but it was taken by his older brother soon afterward.” It makes his brother sound selfish, but the full story is different. As John recalls: “My brother Cass plays guitar and he got me started playing. I had already started playing banjo and loved Scruggs style and the melodic style, as well as clawhammer and Seeger styles. We listened to the radio growing up and I loved the Beatles and Elvis but didn’t really think that I would ever do music for a living. I got a guitar for Christmas, but my hands were too small and the strings were too far from the fretboard so my brother took it and carved his name in it. I learned quite a few chords from my brother and he was very generous in lending me songbooks and knows a lot about music. He still plays and is serious about music.”

John’s interest in the banjo was considerable. As he describes it: “My first banjo books were Earl Scruggs and the 5-String Banjo which also had a companion record album, and was very helpful. I wrote Earl a fan letter when I was 15. The other main book was Pete Seeger’s book How to Play the 5-String Banjo. Later, Tony Trishka’s book Melodic Banjo was a big deal for me.”

The guitar soon re-entered the picture and the songwriting began as well. John recalls: “I started playing guitar about 6 months after picking up the banjo. I started trying to write songs right away. It seemed that my songs sounded better to me than the versions of other people’s songs that I was trying to learn. I don’t mean they were better songs, but they sounded better because they were within my very limited range of ability.’

He played in a folk group at church. In March, 2010, the web ‘zine NJMonthly.com posted a story by Robert Gluck called “Home Again” subtitled: “Folksinger John Gorka has never stopped being a Jersey boy.”

In it, Gluck quotes Jennie Esposito, who ran the folk group: “Jennie Esposito remembers her first encounter with John Gorka. He was a shy eighth-grader in Colonia who had been invited to join her church folk group. ‘When he spoke, it would take him a long time to say what was on his mind,’ Esposito says [some things never change]. Then she heard him sing. ‘We were thrilled to have him. I gave him a lot of solos.’”

There were additional performance experiences as well. John stated: “I played in the band for a production of ‘Free To Be You and Me’ in high school and was a performer in a production of ‘Godspell’ in church in addition to being in the church folk group.”

College and Godfrey Daniels

John attended Moravian College in Bethlehem, Pa., where he studied philosophy and history and received a B.A. He kept honing his skills, playing open mics immediately after getting to Moravian. He made friends with mandolinist Russ Rentler and guitarist Doug Anderson. Together, they formed the Razzy Dazzy Spasm band. Richard Shindell would join them around a year later. Doug Anderson introduced him to the Godfrey Daniels coffeehouse. Doug was dropping off a record for a friend to get him a gig there. John states in an interview I found online: “People were sitting around the front room passing around a guitar. It came to me and I played a song. I thought it was what Greenwich Village must have been like in the early ‘60s. It was a little slice of Bohemia right there on the Southside of Bethlehem, Pa.”

At some point, after graduating from college, he lived in the basement of Godfrey Daniels for a few months. He ran the sound board and acted as m.c. He became the house opener for many acts that passed through, learning from them all. It’s there in his song “That’s How Legends are Made,” written about the great Canadian folk singer, the late Stan Rogers and his brother, Garnet. “I worked at a place where the bands came through / some of them rang false and some rang true / I’d stick around after they played / to learn how legends are made.”

When his first recording came out, his voice had a deeper sound, similar to that of Stan Rogers. He says that Stan made an impact on him and that he inadvertently absorbed Stan’s vocal style. It’s fun to contemplate what kind of impact the big baritone of this newcomer must’ve made on audiences back then. Among the many John learned from he cites, “to name a few,” Claudia Schmidt, Roselie Sorrels and Dave Van Ronk. When he headed out on tour, taking his songs and big voice out on the road, some of those he’d opened for, opened doors for him.

The first performer John opened for at Godfrey Daniels was Jack Hardy. He learned about Jack’s New York song swap group and the principle that you could improve as a songwriter by writing one song per week and playing it for the group, whose attendees would give feedback. At Jack’s urging, he moved to New York and became one of the Fast Folk Musical Magazine’s greatest co-operating musicians, and one of its more well-known “graduates.” Emusic lists John as being a contributor on 14 of the Fast Folk Musical Magazine recordings. There were many associations and friendships that developed in New York. Cliff Eberhardt, Lucy Kaplansky and Christine Lavin were among them. John remembers that David Massengill was one of the steadier attendees at the song swap.

I mentioned to John that he shows a great amount of empathy in his songs and asked how it developed and if the Fast Folk experience enlarged upon that. He replied: “I know people started taking notice of my songs when I started to write about the neighborhood around Godfrey Daniels and some of the local characters. I think Jack and the Fast Folk experience inspired me as well. I think our purpose in this life is to become other-centered.”

When I asked about some memorable experiences during this time, John recalled: “I remember singing on a tabletop with Shawn Colvin at the first Falcon Ridge Folk Festival in 1988. It had started to pour rain and everyone moved into the ski lodge (the festival was held at the Catamount Ski Area). The festival people were afraid that everyone would leave if there were no music, so we sang.”

In 1984 he won the New Folk Award at Texas’ Kerrville Folk Festival. He continued to sharpen his skills, and in 1987 released his first album, I Know. He had studio support from fellow Fast Folk players Shawn Colvin and Lucy Kaplansky.

Literary Influences

Novelist and short story writer Richard Ford, a Pulitzer Prize winner, was a new name to this author. His work seemed especially pertinent, given his elegant use of language. I’ll be reading everything by Ford I can get my hands on. Thanks, John!

On John’s latest CD, So Dark You See, William Stafford’s anti-war poem “At The Un-National Monument Along The Canadian Border” was interpreted for the song, “Where No Monument Stands” “This is the field where the battle did not happen / where the unknown soldier did not die / This is the field where grass joined hands / where no monument stands / and the only heroic thing is the sky.” If governments were run by intelligent men, there would be no need for war heroes. Or monuments.

Other Favorites

We can only scrape the surface of this impressive repertoire. In the beginning there was “I saw a Stranger with Your Hair.” It’s on his first album, I Know and is listed as one of the tracks on the first Fast Folk Musical Magazine recording. Its uniqueness at describing the loss of a lover was something new: “And by the way, how is my heart / I haven’t seen it since you left / I’m almost sure it followed you / Could you sometimes send it back? / I’ll buy the ticket.”

Then there’s the aforementioned “Love is Our Cross to Bear,” from the same album. “I want to be a long time friend to you / I want to be a long time known / Not one of your memory’s used-to-be’s / A summer’s fading song … I am here, you are there / Love is our cross to bear.”

On 1990’s Land of the Bottom Line, there’s “That’s How Legends Are Made” and the wry ode to his stolen car, “Stranger In My Driver’s Seat:” “I lost my car to the Riverside Drive / Last seen headed up the Upper West side / 138th Street or 139 / What’s yours is theirs / What’s theirs was mine.”

The album Jack’s Crows was released in 1991, and the title track caused some speculation among some of us who thought it might be about attendees of Jack Hardy’s song swap and their sharp critiques. “Jack’s crows are loud in the morning / They’re critical of other birds…” I didn’t ask if there was any truth to this and I suspect that John would like to leave it a mystery.

That album, especially rich in groundbreaking lyrics, also contained “Silence.” I met her in the summertime / When her arms / Were the color of silence / So blue her eyes / A new horizon.” “Semper Fi,” about his father meeting Eleanor Roosevelt, is heartbreaking in its concise statement about the aftermath of war. “Some of the men who did survive / Were not the lucky ones / War is only good for those / Who make and sell the guns.” “I’m from New Jersey,” presents John’s origins with comedic modesty. “I’m from New Jersey / I don’t expect too much / If the world ended today / I would adjust…” “Night is a Woman” presented a longing in words no other folksinger uttered: “Night is a woman who embraces me / I am never lonely in her arms / Deep in her heart I am free from harm.” The entire album was one home run after another. The favorites cited here simply resonated a bit more with this author.

On the album Between Five and Seven, released in 1996, my favorites include “Lightning’s Blues,” “Blue Chalk,” “Can’t Make Up My Mind” and “The Mortal Groove,” on which I keep hitting the repeat button. A rumination on beating back the spirit-deadening aspects of life, it is somber and poetic: “…Countless souls in unkind places / Wearing fixed and angry faces / I tell myself I don’t belong / But I am a ghost in this prayer gone wrong...”

His 2006 CD Writing in the Margins included themes that strike deep into the heart on both a national and personal level. The title track is a response to a meeting with a soldier after one of his concerts. The soldier is writing to his wife from the battle zone: “I am writing in the margins / Cause our days are spoken for / And your nights are with the restless / Who were broken in this war…” Although it’s John’s personal response, by telling this soldier’s story, he also pays homage for all of us who never strapped on a helmet and walked into harm’s way.

The album also contains a cover of one of his favorite Stan Rogers songs, “The Lock Keeper,” an eloquent musing on the sacredness of home life. A ship is passing through the lock and the sailor exhorts the lock keeper to free himself and follow him. The lock keeper replies: “Ah your anchor chain’s a fetter / And with it you are tethered to the foam / And I wouldn’t trade your whole life for just one hour of home.” A favorite moment for John occurred at one Boston Folk Festival in a workshop with Garnet Rogers about “Songs We Wished We Had Written.” John recalled: “I played Stan’s song ‘The Lock Keeper’ and Garnet played the electric guitar part he played on Stan’s album From Fresh Water. I was thrilled that Garnet was playing along with me.”

The recently released So Dark You See (2009) continues to explore familiar themes. “Whole Wide World,” the first track, asks what an angry failure living on a dead-end street might do if he could have another chance at a lost love. The achingly beautiful “Can’t Get Over It” mourns a lost friend, calling forth the ghosts of 9/11. There are two instrumentals on the album, “Fret One” and “Fret Not.” Recording in his home studio allowed John to explore the sheer joy of letting an instrument do the singing. The song, “Ignorance and Privilege,” was sparked by Molly Ivins’ remark about George W. Bush: “George was born on third base and thought he hit a triple.” However, the song is about all of us who thought that our status as white and middle-class entitled us to a college education and an easy path to riches: “I didn’t know it, but my way was paved.”

The voice of the late Utah Phillips precedes John’s cover of Utah’s “I Think of You,” Exhorting John to sing his song, we hear: “That song, there… I’d

really love to hear it coming out of John Gorka… John, can you hear me now?” It was a smart move, Utah.

Like most singer/songwriters, John repeats certain musical themes. However, there are elements that prevent his work from getting old: mastery of language and the ingenious way he combines phrases. We’re witness to a perfect marriage of melody to words and, of course, that astonishing instrument, his voice.

Today, John lives in Minnesota, is married, and has two children, 12 and 10 years old. Although a world traveler, he has obtained the treasure that the lock keeper held so dear. While there may be dark days and dark moods, he will deal with them the way he always has. The songs will get him through. His sharing them will show us the pathway through the darkness in our own lives.

Upcoming appearances include:

Jul 18pm One Longfellow Square

181 State St., Portland, ME $22

28pm Club Passim Cambridge, MA $30/28

3, 4New Bedford Summerfest New Bedford, MA

9Great South Bay Music Festival Patchogue, NY

108pm Katharine Hepburn Cultural Arts Center, 300 Main St.

Old Saybrook, CT $25

117pm Caffe Lena, Saratoga Springs, NY $25 Adv / $22 Door

23, 24, 25Falcon Ridge Folk Festival, Hillsdale, NY

24Guthrie Center, Great Barrington, MA

Website: www.johngorka.com