Wool&Grant

Wild Women Don’t Worry…

By Richard Cuccaro

It’s difficult to express how much enjoyment I got out of hearing the old chestnut, “Wild Women,” written by Ida Cox and sung by Wool&Grant on a recent John Platt Sunday Morning Breakfast Show on WFUV-FM. The song is one of a host of gems from their new self-titled debut CD. I knew it was Ina May and Bev because I’d heard them before and their sound is immediately recognizable. There’s something of a country twang in Ina May Wool’s voice that increases the veracity in her songs about life’s travails and victories. There’s a Buffy Sainte-Marie-like quaver and a power in the voice of Bev Grant that helps raise a person’s social awareness when it happens to be her goal. Together, Wool&Grant possess a sweet blend and a one-two punch that invites all kinds of “strong women” references.

Their joined voices provide a wealth of pleasure, no matter what direction their music takes them. Their combined experience and backgrounds add to their vocal affinity. Both women started making music when they were very young and both of their paths make fascinating stories. The song, “Wild Women” is a perfect fit for them and I found out why. There’s been plenty of wildness in their lives.

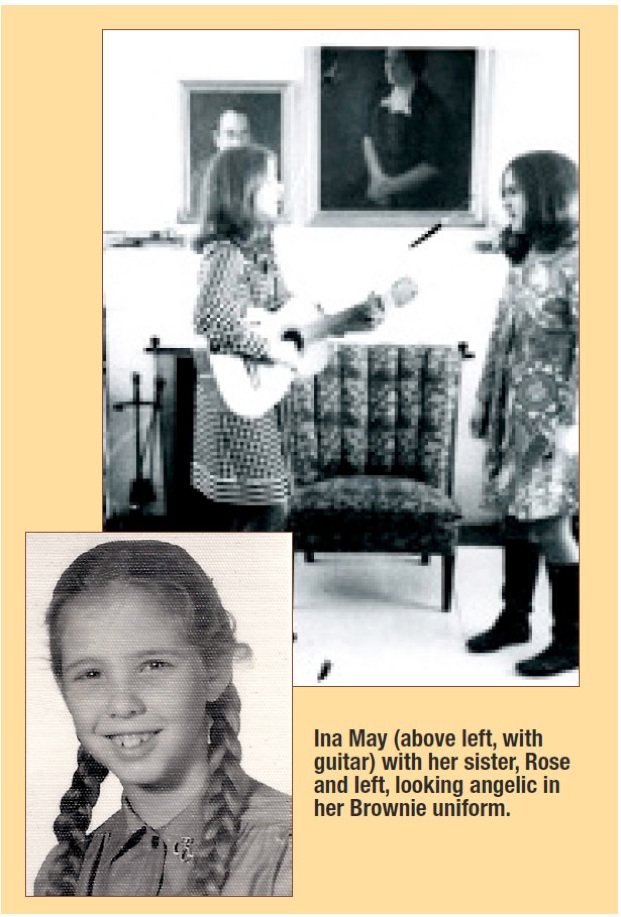

Ina May Wool grew up in Marblehead, Mass. She got her musical baptism from her parents, both of whom were artistically inclined. Ina May told me they honeymooned for a week in New York City and saw a musical each day. Her mother graduated from Massachusetts College of Art in Boston and was an oil painter and then later a prolific printmaker. Her father loved art and was a photographer with a great eye. “Both of them loved to sing, and we sang on trips in the car and around the house,” she said.

One anecdote offers an early glimpse into Ina May’s future: “My mother heard me singing one of the more complex songs from Peter Pan (on TV when I was about 6), and was impressed with my ear — she showed me what the melody I was singing looked like on the piano and told me it was not an easy song to sing.”

Ina May started guitar lessons when she was 9. Her teacher, George Walkey, hired her as a helper for his group guitar lessons at the Marblehead Y. She would help tune students’ guitars and at the end of the class, would sing and play a song. Ina May took liberties with the songs she learned from records. She remembered playing a song one week she’d heard on a folk record, prompting the following dialogue: “‘Where’d you get that song?’… ‘It’s on a Kingston Trio record.’ … ‘Uh-huh,’ said Mr. Walkey, man of few words, giving me a look. Later I realized that when you change the words, the chords, the melody and the rhythm of a song, it might be called ‘writing’ a song. At the time, I thought everyone did that.”

A Budding Professional

A big formative experience came from Ina May’s connection with a member of a friend’s family, Davidine Small, whose mother and uncles were vaudevillians and musicians. During their visits from New York, everyone made up songs and wrote plays, then performed them. Although she can’t be sure, Ina May thinks that Davidine might have helped her get her first local gigs. She played kids’ parties in junior high and high school and would get $10 for each party during which she’d lead singalongs.

One of Ina May’s big money gigs was the town Christmas party at Abbott Hall in downtown Marblehead. “I roamed around the party singing Christmas songs, stuff from Mary Poppins and other songs, and they paid me $50. Huge money. I wanted to be a working performer.” Ina May was a voracious reader and wrote poetry. She also went to the library and took out all the books on how to write songs. “I think there were three old musty tomes from way back in the stacks, mostly about Tin Pan Alley kind of songwriting. I was trying to figure it out.”

After high school, she moved to Manhattan and went to Barnard College, the women’s school affiliated with Columbia University. She played the venerable Postcrypt Coffeehouse and other concerts on campus, opening at one point for legendary jazz pianist and composer Mary Lou Williams.

Getting the Gigs

In a short-lived episode after college, Ina May moved to Santa Cruz, Calif., to continue working in a rock band with her boyfriend. The band didn’t rehearse or play anywhere, so she moved back to Massachusetts. At this point, her life got busy.

As she described it: “I booked myself at coffeehouses and colleges as a solo act but after a few months, the bass player from the rock band moved to town from where he’d been in California to play with me. A drummer he’d met in California also moved in, and we met some local musicians, and we started doing some of my solo gigs as a band.

One of my solo gigs without the band was at Sandy’s (also a famous jazz club) in Beverly, Mass. I opened for Paul Pena who wrote (Big Old) ‘Jet Airliner.’ He invited me to sing with him that night, and I jammed with him onstage. Paul Pena’s producer and booking agent were there and approached me about working with them. Over the next few years, my band and I played all over New England, from northern Maine, to as far east as Reading, Pa., and as far south as D.C. I worked at Passim’s, opened for David Bromberg, Paul Winter Consort, Maria Muldaur, Janis Ian, Tom Rush, David Amram … basically everyone.”

A song vignette of this period, full of humor and heartbreak, “Here We Go,” is included on Ina May’s second solo CD, Crack it Open:

Now you’re up north / For a week in a ski lodge

In July it’s one hundred degrees / In that place

Five sets a night / When you know all of eight songs

Will lead you to make up some songs / Right away

Try to avoid falling in love / With anybody in the band

You are high, you are low, here we go

After you break up with the bass player

Learn how to drink a quick glass of Jack

When it’s time to go on and you think you might cry

Then have the time of your life playing music

Laughing so hard that you fall on the floor

Opening shows for the once nearly famous

Concerts and TV and agents galore

Try not to crash and burn on re-entry

When the band breaks up

You are high, you are low, here we go…

Live from New York

Eventually, the band did break up. She got a manager who also managed Jonathan Edwards. When he moved to New York, Ina May followed and she opened for Jonathan a few times. She didn’t play acoustic for a while and hung out with rock musicians, did studio work and was in a rock opera, The Last Words of Dutch Schultz. She wrote a song for her part as Dutch’s wife.

As she saw it: “I missed playing out live and New York gigs were always high pressure showcase kinds of things. Musicians that I knew were able to play “club” dates, weddings, anniversary parties, bar mitzvahs, etc., and I thought it would be good for me to get better as a singer and to learn material, not just work in a band based around me — and to earn money. [Progressive rock/jazz guitarist] Marc Ribot [he’d lived in a factory town in Maine and knew about Ina May from her gigs there] told me about the scene and surreptitiously taped hours of these ‘continuous music’ gigs so I could learn about it. He told me who to call for work, etc. It was a whole other world, some rock and pop and also some standards and jazz singing with pickup bands. [At that time] I was going through a very bad break-up.”

This would change abruptly when she met accomplished musician Daniel A. Weiss, who became her husband. The gig organizer told Ina May that “Danny Weiss would be playing the evening gig and was a genius.” Ina May was skeptical. She got to the gig later than usual, although still on time. Another band person was explaining to Dan how Ina May sings “this song” and “that song.” Daniel said in response (not aware that Ina May was standing there) “Oh, I know all that female stuff!” Ina May stepped up and said, “Oh, really? Are you married?” and wound up telling him about her relationship problems after the gig. At the end of the evening, he handed her a promo postcard, telling her that he’d be playing her neighborhood, if she “still wanted to get married.” [Photos of Ina May leave no doubt as to why he might give this idea serious thought on such short notice.] He was playing backup piano for a jazz singer on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. She’d only heard him doing pop and rock on synthesizer at the gig and was flabbergasted to hear him playing “gorgeous acoustic jazz” on a piano. They’ve been married 25 years now and Daniel has produced both of Ina May’s solo albums.

The next change in her life came through her friend Jon Albrink, a session player and singer who also had bands playing his original music. He introduced her to the Fast Folk Cafe open mic (which I was running at the time). “Jon was working on writing and performing solo acoustic songs, and he had started going to various open mics. He said he’d go with me, and so he introduced me to that part of the scene.” Ina May’s career as a solo singer/songwriter entered its next chapter.

A Sister Act

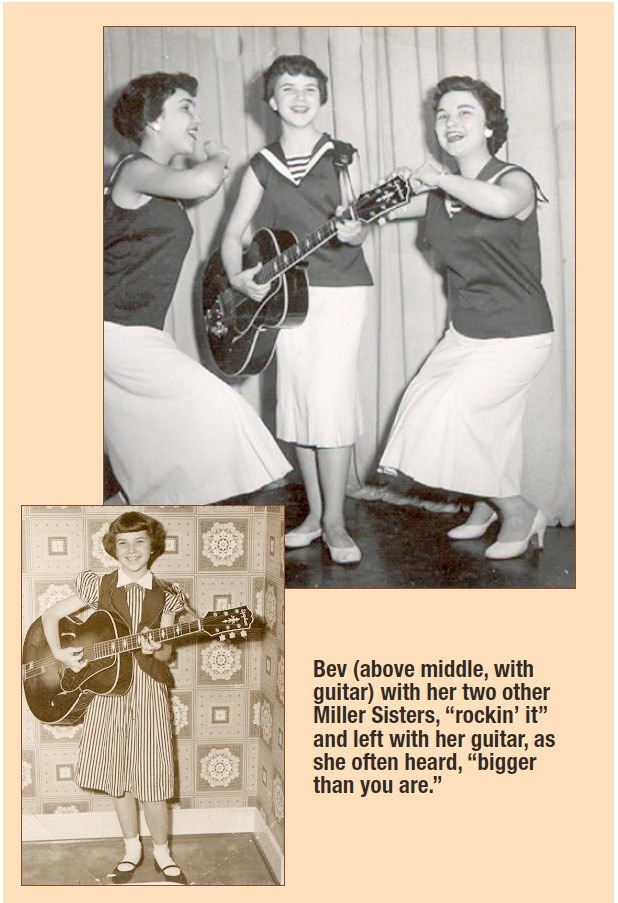

Bev Grant grew up in Portland, Ore. When she was 10 years old, her father gave her a guitar instead of the bike she wanted. In hindsight, this proved to be the right gift. She took guitar lessons at a music store in downtown Portland. She had two older sisters and they each started playing instruments and singing. Her oldest sister had taken several years of piano lessons and learned electric bass, while her middle sister took up lap steel.

They formed a trio and began playing at music school recitals. Her oldest sister bought some stock arrangements and that’s how Bev learned to sight-read music. Their trio was called The Miller Sisters. The three girls combined a mixture of styles. Bev was known as “the little girl with the big voice,” and sang songs like “Blue Suede Shoes” and “Heartbreak Hotel” as well as Teresa Brewer covers. Her middle sister was doing standards like “A Pretty Girl is Like a Melody” and her oldest sister had a light opera voice and sang songs like “Grenada.”

It was the era of singing sister acts such as The Lennon Sisters (The Lawrence Welk TV Show) and The McGuire Sisters (The Arthur Godfrey TV Show). They played together for about five years, appearing five or six times on a local TV country music program, “The Heck Harper Show.” [Upon reading Willie Nelson’s biography, Bev discovered that he appeared on that show during the same period The Miller Sisters had.] Bev told me, “Heck played a big white hollow-body f-hole Gretsch with a whammy bar. She said Heck’s pedal steel player might have been the best she’s ever heard.

Changes

As with most groups, time has a way of bringing attrition. The oldest sister got married and left. The remaining two replaced her for a short time. Then the middle sister left and Bev was left to perform by herself. She sang through high school and had a boyfriend who was a jazz musician. They got married when she was 19. Abruptly, her husband and a bass player friend moved to New York, where they looked for gigs. So, Bev packed up all their wedding gifts and followed him. She got a steady 9-to-5 job to support her husband so he could be a full-time musician.

Bev felt intimidated by the jazz people who surrounded her and stopped doing music for a time. She listened to the greats like Billie Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald and thought “I can’t do that.” She played the role of the musician’s “old lady” for a couple of years and then ended the marriage. After that, she lived with a drummer who was known on the scene but was abusive to her. It took her a while to extricate herself from that relationship, but she managed to do it around 1966.

Finding Herself

She was finally on her own and became involved with protesting the Viet Nam war and in overarching societal problems.

She got introduced to and became heavily involved in the women’s movement, resulting in a greater level of self-awareness. It was liberating for Bev to finally see her own involvement in an abusive relationship as part of a greater issue. She took up photography and took photos to heighten social awareness. She also joined a filmmaking group that was making political documentaries. As part of that group she made a documentary about the Miss America pageant protest in 1968 and she took many photos surrounding that event.

She had taken her guitar out again and wrote parodies illustrating the protest. One used the song “Ain’t She Sweet.” This snowballed into her writing an avalanche of songs that she now laughingly describes as: “Let’s take it to the street; let’s make a revolution!”

In 1972 she had her first child and formed the folk/rock group The Human Condition. They recorded two albums. The first, recorded on Paredon Records, had a lot of feminist material, she told me. She learned to use the concept of “story songs” to make a political point, and on the first album, wrote about a working-class woman, “Janie,” from Ironbound, N. J., who declares, “I’m Janie’s Janie, not daddy’s Janie, not Charlie’s Janie.”

Bev gave birth to her second child in 1982 and The Human Condition re-formed as a world-beat band, singing in different languages about international struggles. The trio became a 10-piece band and lasted until 1991. Always a high-energy person, Bev had a full-time job and was a single parent throughout this time. [She retired six years ago from The Osborne Association, a not-for-profit which helps prisoners transition from incarceration. She has written songs to illustrate those issues.] After the Human Condition disbanded, she formed the Brooklyn Women’s Chorus, a 40-person vocal group.

Ten years ago, Bev formed a trio called The Dissident Daughters with two women were recruited from the Brooklyn Women’s Chorus. The group put out one EP called Cheeky Women.

Wool&Grant at Last

Bev’s involvement with Ina May evolved from a Dissident Daughters recording project with Ina May’s husband Daniel. The project never went anywhere, but Bev and Ina May had gotten to know each other through a song writing workshop and started singing together. Their first gig as Wool&Grant was a co-bill with Bev and The Dissident Daughters at The Good Coffeehouse in Brooklyn.

The bond between them strengthened as they participated in a workshop on memoirs. They got to know each other’s life stories and saw that they had similar sensibilities as young performers.

While Bev brings a higher political sensibility and Ina May writes a greater amount of personal songs, they complement each other. Bev brings songs to Ina May for feedback and feels her songwriting has improved. “She pushes me,” said Bev. Ina May has learned more about harmonizing from working with Bev, who is still a choral director. While Ina May focuses on rhythm guitar and finger picking, Bev has taken on lead guitar work. They’ve each brought earlier work to the new album and have collaborated on one of the new songs, “The Last Man on the Mountain,” about strip mining. Bev’s song “Get the Frack Outa Here,” is an instant classic.

In an effort to gain greater perspective, I looked for other reviewers’ opinions of Wool&Grant and ran across this one on Sonicbids: “In addition to the feistiness they inject into songs about the battle between the sexes, there’s the social awareness avenue exemplified by “Get The Frack Outta Here.” With lines like, Natural gas, kiss my natural ass / Get the frack out of here, I’m glad they’re on our side. They’ve been a team since the beginning of 2011, so it’s a little late, but… ladies, consider this an official “Welcome.”

Oops. That was my own, about their pre-release of the new CD, reviewed in our December issue. I can’t disagree with myself and I hope you won’t either. Go see two wild women and get happy.

Upcoming performances include:

Jul 12 Bev & Carolann Present 2nd Fridays @2Moon, Brooklyn

Aug 3 Falcon Ridge Folk Festival, Hillsdale, NY

Website: woolgrant.com