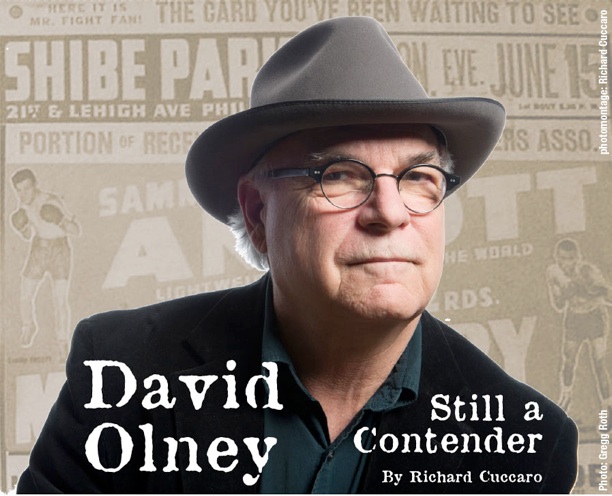

If you like your musical heroes to rock out like the jackhammer of a rockabilly saint but also deliver song sonnets from a contemplative place, then David Olney is your man.

In 2006, he appeared at the New Bedford Summerfest Folk Festival. I approached him for a cover article, but didn’t follow up. Embarrassing. Olney is probably one of the top five singer/songwriters alive. He’s been called “Nashville’s answer to the Bard.” Many singer/songwriters get absorbed with angst over the demise of their love affairs and other emotional potholes. David Olney occupies himself with inventing stories for other entities. On his latest release, When the Deal Goes Down, in the title track, he exhorts God to re-examine his priorities: You don’t have to raise the dead / Give wine or give me bread / Just tell me you’ll be there when the deal goes down. “People need to feel their life has meaning and that they’re loved and accepted when the deal goes down.”

Nine years late, here we are, getting ready to welcome him again to New York City (On March 13, another show at Kathryn’s Space — a Nashville-Austin pipeline). It’s time to get ’er done.

Roots

David was born in Providence, R.I., in 1948 and grew up in the village of Saylesville within the town of Lincoln, near Providence. He describes his childhood as “idyllic.” In that small, tranquil town, in 1950s America, his school gave dance classes. He plied his paper route and could cut through the woods on a daily basis to get to his best friend’s house when he was only 8. “Who would do that now?” he asks. He finds these aspects of his childhood largely absent in today’s culture. His entry into life as a performer came when he quit the basketball team to take part in a school play. His love of theatricality sprang from the first moment he stepped on a stage with a room full of adults waiting to hear what he had to say.

For the young, being “cool” is paramount. David loved singing to stuff he heard on the radio.That was cool. “Roy Orbison just tore me up.” Although he found singing in school embarrassing, on his early morning Sunday paper route, he’d belt out, in full voice, songs he learned from the radio.

When he was 13, he got a guitar for Christmas, and after some lessons, could play a “really rousing version of ‘Row, Row, Row Your Boat.’” David’s older brother, Peter, had a record collection with a lot of blues and bluegrass music, and it made a big impact. Later, David learned how to play “What’d I Say” from a Ray Charles record in Peter’s collection while he was away at college. David practiced “like a slave” to get the bass line down and then would play the song in front of a mirror, figuring, “It would make me look cool.”

His mother’s side of the family came from Linville, N.C., near Grandfather Mountain. They’d travel to see them nearly every summer. David came to view the South through the lens of family, rather than the prevailing ’60s view of Southerners in sheets, eager to lynch the errant person of color. When he got into music, most of his favorite songs were connected to the South. Both his brother’s record collection and visiting his Southern relatives infused in him the love of folk music. “Folk music was a big deal back then and so much of the folk music came out of the South. You didn’t need a whole band. If you knew a few songs and learned a couple of chords, you could go someplace and play those songs.”

The Chapel Hill Launching Pad

After graduating high school, David attended the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. His major was English literature. “I thought I’d better stay with my native tongue … anything outside of that I felt I was going out on a limb.” The music scene took over his life and he dropped out after one year. An enterprising woman, Marcia Wilson, moved to Chapel Hill from Maryland and opened a cafe, The Cat’s Cradle. “It was a magnet for all the musicians and songwriters at that time. It became the center of my life.” Performing there, David began sliding his own songs into the middle of a set of Carter Family songs and the like, figuring if no one noticed, he’d written a good song. He also became a member of a jug band.

Simpson, a Brief Education

After dropping out of school, David had a job working in a candle factory. A fellow UNC dropout, newly married musician friend, Bland Simpson, asked if David could get him a job there. They worked nights, mailing out boxes of candles and talking music. Bland told David he was going to New York to get a record deal. This was a revelation to David, who didn’t know anything beyond playing small gigs locally. Later, when Bland asked David to play guitar in his band, David jumped at the offer. His time in Simpson lasted about a year. He was part of the release of one album, the eponymous Simpson (1971), and he learned a lot about the music business during that brief time.

A Pit Stop in Atlanta

After the year with Simpson ended, David moved back to Chapel Hill. He fell in love with a woman who was going to Atlanta to pursue a law career. A friend from Chapel Hill, Ben Jones, was acting in the Atlanta Children’s Theater and got David a part in a play, which parlayed into a steady gig, enabling him to stay in Atlanta with his girlfriend. The affair ended and, after a year-and-a-half in children’s theater, David left for Nashville.

Nashville, the X-Rays and Beyond

For a man who today has more than 30 albums to his credit, containing many songs considered masterpieces, things took a while to jell. He’d been writing sporadically and had been advised to test his craft in a milieu that would allow him to gauge his prowess. “I knew a few people and had a couple of couches to crash on.” He began writing more deliberately, start to finish, rather than purely by whim, as he’d done in Atlanta. “That’s when I became a songwriter.” David assembled a group of players he intended to be a country band but couldn’t get together to rehearse. He had to bring his songs around to each band member in turn to learn. They didn’t find out exactly what they sounded like until they played their first gig. With drums, they turned out to have a rock ’n’ roll sound. They had no name — just “David Olney and his band.” The fiddle player quit right away and David recruited an electric guitarist. At that point they became the X-Rays. Their first album, Contender, was released in 1981, the second, Customized, in 1984. There are videos of the group from the Austin City Limits TV show on YouTube, showing a youthful David Olney, as a rocker, leading the band through a wide range of material. When David performed the title track of Contender, about a rising fighter whose loss is life-changing, he walked out into the audience and acted the lyrics out, his head snapping with each punch, collapsing to the floor as he sang … my knees buckled and they turned out the lights / they turned out the lights … then got up and sang: I could have been a contender / Now can you say the same? The audience gave him a standing ovation. Many who adore the group return to watch the clips over and over. David told me, “I saw myself as in the rock ’n’ roll business. The songs were written for the band.” However, some songs from this period, like “Contender,” “If Love Was Illegal” and “I’m Gonna Wait Here for the Cops,” have survived as tracks on his later, folkier albums.

Legacy

His first solo album, Eye of the Storm, was published in 1986. His second, Deeper Well, in 1988, from which Emmylou Harris covered the title track on her Grammy Award-winning album Wrecking Ball (1995) and essentially ushered David into the front ranks of Nashville songwriters. Emmylou also later recorded David’s “Jerusalem Tomorrow” and “1917,” about a French prostitute who provides solace to a young World War I soldier. Its lyrics capture the horror of war — death in the trenches and too many corpses to bury. Its desperate refrain, tonight the war is over, brings home the futility of pawns in the clutches of a conflict between world powers. In “Jerusalem Tomorrow,” a charlatan, peddling fake miracles, is told about the exploits of Jesus and tracks him down. Deciding to join him, we hear: Don’t see how too much can go wrong … We’re headed for Jerusalem tomorrow.

When he begins the titular song of his album Roses, about the endurance of a sturdy old oak, split in half by lightning, then blossoming roses, I hear the rolling notes peel away from the fret board and I already know what’s coming: The old oak tree began to shudder / But he held his ground like some old soldier / His ancient pride was burnt and shaken / But something deep inside did waken / He raised his limbs just like Moses / And blossomed roses. My throat constricts and my eyes fill. The beauty of the melody and the elegance of the lyrics are a mixture of ecstasy and sorrow, capturing the rages of fate and nature and the brave transfiguring resiliency of their survivors. While there’s a perfectly lovely studio version on YouTube, I prefer the completely acoustic performance on his website “News” page, done for the The Nature Conservancy’s If Trees Could Sing project.

David, by himself, in all his complexity, is almost more than one can handle. Furthermore, videos from Hippie Jack’s Music Festival show David in the company of monster guitarist Sergio Webb. Here, his craft seems to take off into the stratosphere. His song’ “Sweet Poison,” with its spoken introduction, blossoms like the love child of Jack Kerouac and ZZ Top.

A Singular Whimsy

David displays an acute awareness of modern songwriting’s place on the historical spectrum. Discussing the sophistication of an earlier generation of writers who’d taken piano lessons as kids, he muses: … “like the Gershwins; George Gershwin was off the charts” … and how things got simplified when the guitar became the main instrument of songwriters, “Making an E flat chord on a piano is no more difficult than making a C, whereas on a guitar, making an E flat is like going to hell.”

David posts a weekly video (every Tuesday since August 2008) on YouTube, Facebook and his website that he calls “You Never Know.” It’s a great way to get a taste of his off-the-cuff humor. He opens each installment with some wry commentary on what’s happening with him and follows it up by playing a song (usually new) with the story behind it.

On the current tour, David is accompanied by bassist Daniel Seymour. If you think you can handle it, sit and bask in the company of the man about whom the late legendary Townes Van Zant said, “Anytime anyone asks me who my favorite music writers are, I say Mozart, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Bob Dylan, and Dave Olney … Dave Olney is one of the best songwriters I’ve ever heard — and that’s true. I mean that from my heart.”

For a more complete picture of this multifaceted artist, visit his website: davidolney.com